TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP via Getty Images

Written by Carren Jao

An amalgamation of rubber, nylon, and synthetics that we walk around in all day, sneakers shouldn’t occupy a special place in our hearts, but they do. For some, it’s about looking good while staying comfortable, but for others, it’s much more.

“I couldn’t have it as a child,” said 21-year-old Avi Ibgui, whose parents emigrated from Israel in the ’90s and didn’t have the budget to purchase pricey items like stylish sneakers. Now a co-owner of high-end Los Angeles sneaker shop HypeLA on Ventura Boulevard, Ibgui is surrounded by these once unreachable fashion items, which he sells to young fashion-conscious college kids, nostalgic Gen Xers, and millennials searching for retro models, as well as celebrities like Ben Affleck and Robert Downey Jr.

Sneakers are a cultural phenomenon. The sneaker market was worth $78.59 billion in 2021, and the industry is projected to grow to $128.34 billion by 2030, according to Grand View Research. The U.S. leads the world market for sneakers at $23.84 billion, followed by China at $18.89 billion, while the U.K. places a far third at only $4.9 billion, according to Statista.

However, not every sneaker holds the kind of power and social significance to command the market. Elizabeth Semmelhack, who literally wrote the book on sneakers (three of them, to be exact) and is also the director and senior curator of the Bata Shoe Museum, told Stacker: “There are so many sneakers made, so many different types of sneakers, but not every sneaker made is valued the same.”

With that in mind, Stacker took a deep dive into the storied histories of some of these game-changing shoes as told in tomes such as “Out of the Box: The Rise of Sneaker Culture” by Semmelhack and “Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers” by Nicholas Smith, as well as interviews and internet research, to see which shoes have moved the needle and why the world continues to obsess over these sneaks.

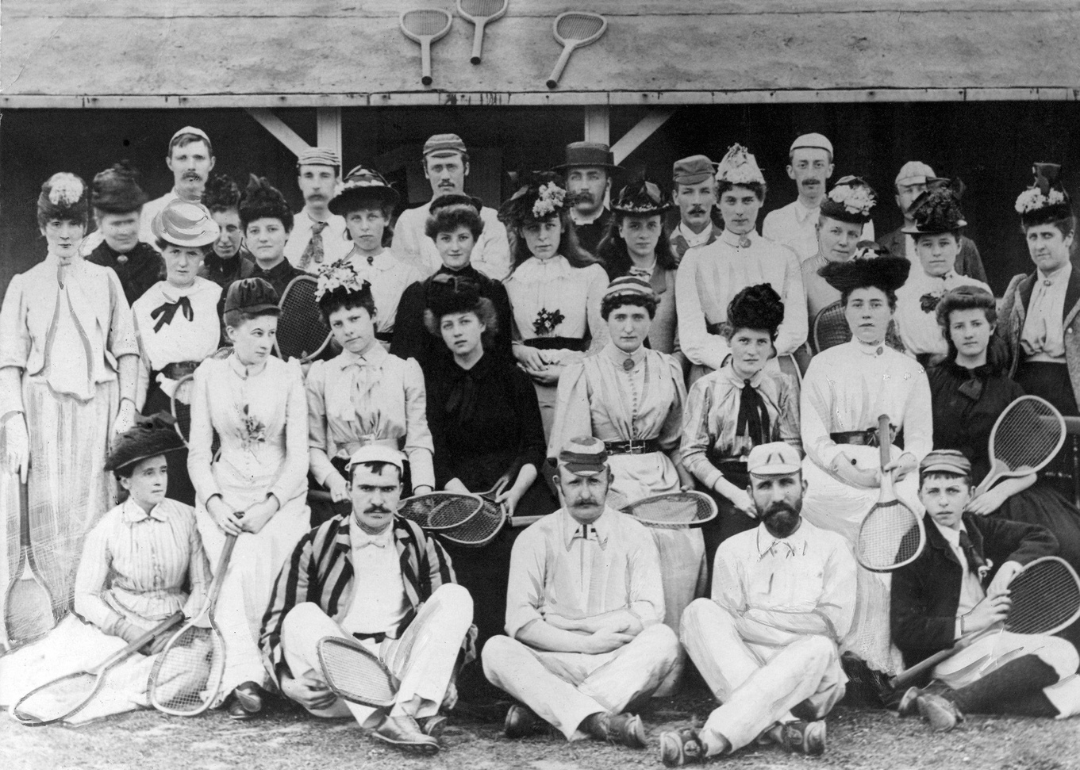

NCJ/NCJ Archive/Mirrorpix via Getty Images

The early days: status symbols and sports

Before sneakers became a must-have in every hypebeast’s closet, they were rubber-soled shoes made for a game of tennis. Around the industrial age, when newly-rich industrialists flaunted their wealth through leisure, they revived the ancient game, adopting the sport’s signature white clothing and rubber-soled shoes to boot, according to Semmelhack. The other theory is that croquet, which was popular around the 1860s, was responsible for the shoe’s increased adoption, according to Smith in his book “Kicks.”

Either way, sneakers were unquestionably birthed as a status symbol. “Rubber itself was extremely expensive. It’s a sap of a tree you can only get a cup from every other day, and only grew in Brazil and certain parts of Central America,” Semmelhack said. “In the first half of the 19th century, a pair of rubber shoes cost over five times the cost of a good pair of leather shoes.”

Later on, the prices of rubber would go down, and sports were bolstered by the idea that physical activity could address the ills of a society in the throes of industrial progress. As the number of people who played sports increased, so did sales for gear and footwear. It was basketball, however, and the Converse Rubber Company, that got the ball rolling in this direction when they hired Chuck Taylor, a basketball player with a knack for showmanship and sales, in 1921.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Sneakers finds its first stars

Author Nicholas Smith titled his chapter on Chuck Taylor, “Johnny Basketballseed,” a clue to Taylor’s outsized effect on sneaker sales. Taylor, who had stints on pro teams by the time he was hired by Converse, was perhaps the first celebrity endorser of sneakers with a high-touch style. His traveling sales/free basketball clinics highlighting his ball-handling skills ended with a challenge to anyone who could stop him from dribbling past. Of course, as volunteers unsuccessfully tried, Taylor would often say, “That’s what the problem is. He doesn’t have Converse All Stars on.”

Converse debuted the All Stars line in 1917 with a high top, a cushioned insole, and a diamond tread pattern. Its now-familiar ankle patch wasn’t just an aesthetic decision but a practical one—it added protection for inner ankles.

Alongside selling All Stars, Taylor was also behind the Converse Basketball Yearbook, which included articles, strategies, and even team photos with players wearing Converse shoes. It was an unrivaled piece of marketing, which became keepsakes for those featured on its pages. Taylor’s effect on Converse was so prominent his name was added to the brand in 1934, along with his signature on the ankle patch, forever cementing these shoes as “Chucks.” That same year, Canadian badminton player Jack Purcell would also get his signature shoe, thanks to the B.F. Goodrich Company.

Austrian Archives/Imagno // Getty Images

Footwear deals with racial politics

Sneakers weren’t just big business on basketball courts. They made a statement on a global scale. At the 1936 Summer Olympics, also referred to as the Nazi Olympics, Black athlete Jesse Owens, who had already broken sprinting and long-jumping records the year prior, wowed the crowds. He handily won the 200-meter dash in 20.7 seconds, a world record. Four days later, he would again win gold and set a world record, this time as the lead in a 4 x 100-meter relay. His performance stood in stark contrast to Hitler’s Aryan supremacy message.

On Owens’ feet? Black track spikes with two distinct black leather stripes on the side made by Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik. A fallout between the founding brothers of the company would birth Adidas and Puma, two brands that continued to compete for athletes’ footwear of choice in global sports events such as the World Cup and the Olympics for decades to come.

It wouldn’t be the last time sneakers became part of a political statement. During the 1968 Olympics in Mexico, sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos wore black gloves and raised their fists as they received their respective gold and bronze medals. A single black Puma sneaker was placed beside each of them. The two used the moment to protest racial inequality and civil rights and created one of the most enduring sports images of the 20th century, according to sports sociologist Harry Edwards.

Kirby Lee/WireImage // Getty Images

Nike: A new shoe empire starts in Japan

After World War II, Japan was in shambles, providing entrepreneurs like Kihachiro Onitsuka an opportunity to build a market from the ground up. At the time, American GIs were popularizing basketball in the Land of the Rising Sun. Hoping to capitalize on this momentum, Onitsuka would design a grippier shoe for a market dealing with post-war supply issues. Inspired by the suction cups of an octopus’s tentacles, he designed the Onitsuka Tiger 1950 OK basketball shoes. (The “OK” from his initials.)

While it made strides in basketball, the company found that running was a larger market. By 1962, its most successful shoe was made for running. These were the shoes eventually distributed by Blue Ribbon Sports, now known as Nike, founded by Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman.

A passionate shoe designer, Bowerman would often influence Onitsuka’s shoe designs by mailing suggestions—one of which was a mashup of two Tiger models with an added arch for flat feet—to Japan. Onitsuka initially named the model the Aztec to honor the upcoming 1968 Olympics in Mexico but later rechristened it to Cortez, the Spaniard who would topple the Aztec empire. The model sold well under the Tiger brand but would go on to become a classic sold under the Nike brand after it won a lawsuit against Onitsuka.

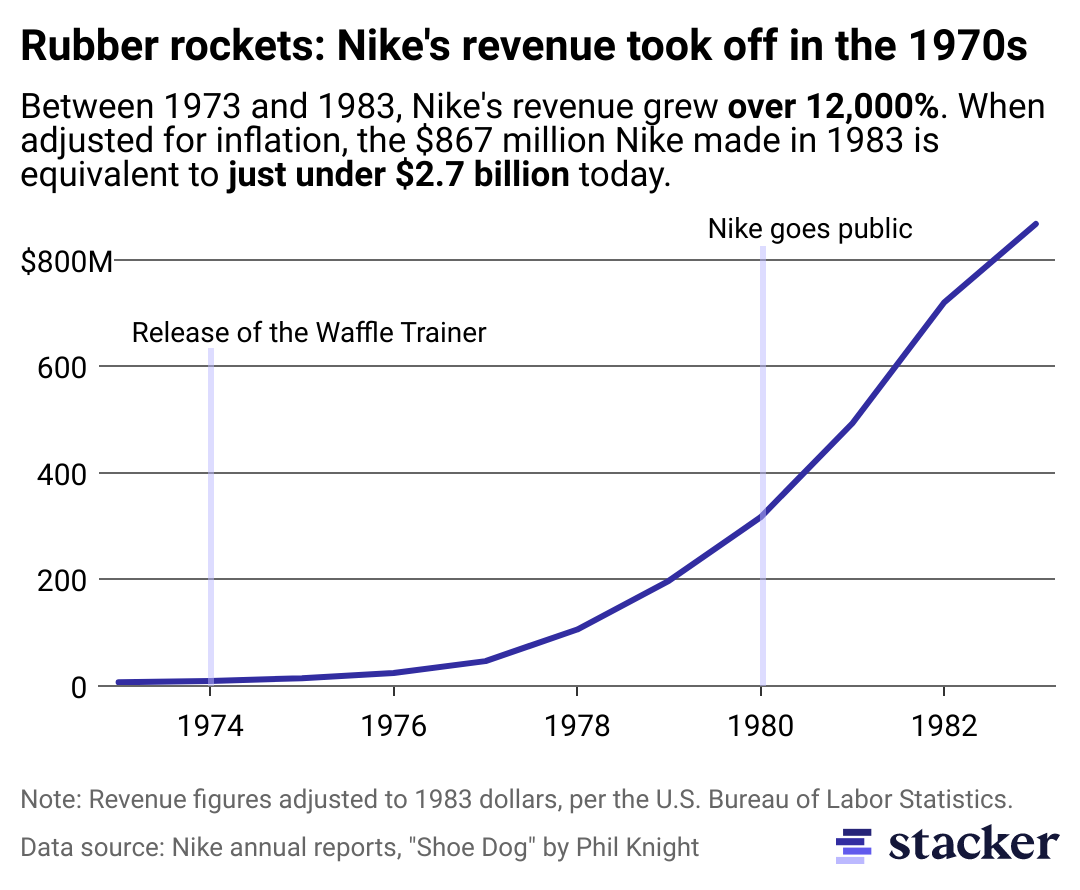

Jared Beilby / Stacker

The Swoosh’s big breaks

Less than a decade later, in 1977, the Cortez would get its big break with actor Farrah Fawcett. In a photograph captured on “Charlie’s Angels” posters, Fawcett rides low on a skateboard wearing a red top and complementary white sneakers with red accents. By noon the day after the episode aired, all stores carrying the Senorita Cortez model she wore sold out, according to Phil Knight.

Nike’s sales continued to climb alongside those of now well-known brands such as Adidas, Puma, Converse, and New Balance, thanks to the jogging boom of the 1970s. By 1976, New Balance would register $1 million in sales, despite taking seven decades before that just to reach $100,000. The next year, New Balance was at $4.5 million.

Jogging would also help boost sales for Nike, who introduced the Waffle Trainer in 1974. The trainer, which provided grip without the extra weight for runners, sold so well that Nike borrowed money just to keep it in production. The shoe’s sales the year after rose to $8 million, with $3.3 million from the Waffle Trainer and other racing flats. It didn’t hurt that Steve Prefontaine, the first athlete to sign with the Swoosh for $5,000, was out there breaking running records wearing Nikes.

Focus on Sport // Getty Images

Welcome, Michael Jordan

Nike owes much of its position as an unquestionable force in the sneaker world to Michael Jordan. Jordan’s partnership with Nike began shortly after his time as a forward with the North Carolina Tar Heels, with whom he hit the game-winning shot in the 1982 NCAA Championship. Rather than spread its efforts on many young athletes, Nike put all its eggs in Jordan’s basket, so to speak. It was a risky move given the poor track record of the often-hapless Chicago Bulls, which drafted the North Carolina native third overall in the 1984 NBA draft.

The risk paid off, and the Nike-Jordan collab on the Air Jordan 1 was a hit. With its high, padded ankle collar and striking colorway—red, black, and white—the shoe called attention to itself, so much so that Jordan was supposedly fined $1,000 (some accounts say it went up to $5,000) each time he appeared on the court wearing them.

Rather than back down, however, Nike pressed on and happily paid fine after fine, eagerly courting sales-generating controversy. Sneakerheads, however, have been doing some sleuthing, saying that Jordan’s banned shoes were probably the Air Ship in black and red. Nevertheless, a month later the first Air Jordan went on sale on April 1, 1985, for $65. The shoemaker earned more than $100 million in revenue and sold almost 500,000 pairs.

While many make a big to-do about these banned shoes, Semmelhack told Stacker that what changed the game for sneakers was Nike’s decision to come out with a new Air Jordan every season, unlike Stan Smiths or Puma Clydes, which were always the same year in and year out. “It helps create the appetite for collecting because it creates a rational framework,” said Semmelhack.

Chris Ryan/Corbis via Getty Images

The tinker and the ballplayer

It was on Air Jordan 3 that the baller would start to work with Tinker Hatfield. Now a legendary shoe designer, Hatfield was once coached by Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman until a severe ankle injury cut his track career short. Nevertheless, Hatfield stayed in the Nike sphere, designing Nike showrooms and offices as an architect and eventually designing shoes, including the Air Max.

The Air Max, inspired by the exposed ductwork and piping in the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, showcased what many Nike shoes kept hidden—its cushioning technology. By creating a window for consumers to see the air cushion on the heel, Hatfield showcased the work that went on under the shoe-design hood.

This innovative spirit is what made him a perfect partner for Jordan. The pair would work on Air Jordan 3 through 15 and then again on XX, XXIII, XXV, and XXIX.

PYMCA/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Sneakers, kids of color, and the nascent world of hip-hop

By then, hip-hop had begun to spread beyond the Bronx. DJs and emcees would sport fly looks, taking their cue from New York City’s neighborhood sneaker-wearing ballers, wrote Bobbito Garcia, the world’s first sneaker journalist, in “Out of the Box: The Rise of Sneaker Culture.” Breaking crews would do their best to outshine each other with fresh moves and an even fresher style. As Garcia noted, “The progenitors of sneaker culture were predominantly people of color—scratch that, kids of color—who grew up in a depressed economic era and experienced a lack of resources. That era, as difficult as it was, was beautiful for me, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

Tracksuits, Kangol hats, and Lee jeans were paired with Converse All Stars, Nike Cortezes, or Puma Clydes. Semmelhack said that while crews had to look the same in what they wore, “it’s at the shoe level where they could express some individuality.”

It wasn’t long before a bigger audience caught on. In 1983, the movie “Flashdance” played in theaters nationwide, giving people a glimpse of the Rock Steady crew’s mesmerizing moves and distinctive footwear. “I don’t think enough credit is given to ‘Flashdance,'” said Semmelhack.

Run-DMC would also come into its own. In 1986, the group’s third album, “Raising Hell,” would become the first hip-hop album to go multiplatinum, buffeted by the song “My Adidas.” Sporting black-and-white laceless Adidas Superstars, Run-DMC would turn hip-hop’s image on its head, singing, “My Adidas only bring good news / And they are not used as felon shoes.”

In a Madison Square Garden concert on July 19, 1986, Run-DMC proved the power of their rhymes by getting thousands of fans to hold up their Adidas shoes right before playing their hit song. This display of the song’s allure convinced Adidas execs to offer the group a million-dollar contract. It marked the first formal contract between a hip-hop artist and an athletic shoe company.

Paco Freire/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Hip-hop’s fashion moguls

The sneaker market today remains full of hip-hop influences in the form of collaborations, which have helped sneakers up the ante on cool. DJ Khaled worked with the Jordan brand, first launching bright red Air Jordan 3 retros with black and gray accents on the heel and toe. Pharrell Williams’ take on Adidas NMDs brings to mind “Happy” vibes, especially in a bright yellow colorway with a white sole and black accent.

Cardi B has teamed up twice with Reebok, coming out with Cardi B Club C and then Carid B Classic Leather. Also in the works is Rihanna’s second Fenty x Puma collaboration. The last two are helping counter sneakers’ male-centric stance. But no other hip-hop artist and creative force has brought so much celebrity and controversy as Kanye West.

An admitted “slave to fashion” in the world of hip-hop, Kanye’s taste and style made its way to coveted streetwear brand Bape in 2007 and eventually Nike with the Air Yeezy 1 in April 2009, retailing for $215 and selling out almost instantly. He would come out with Air Yeezy 2 in June 2012, only to sign with Adidas the next year. From his first Yeezy 750 Boost for Adidas in 2015 to many models and colorways since, West’s sneaker designs have garnered him millions.

Based on his Federal Election Commission filings, Yeezy LLC, Yeezy Apparel LLC, and Yeezy Footwear LLC are each worth more than $50 million. Of course, since Kanye engaged in a series of antisemitic comments and posed in a “White Lives Matter” T-shirt at a fashion show, many businesses have cut ties with him—including Adidas.

Jared Beilby / Stacker

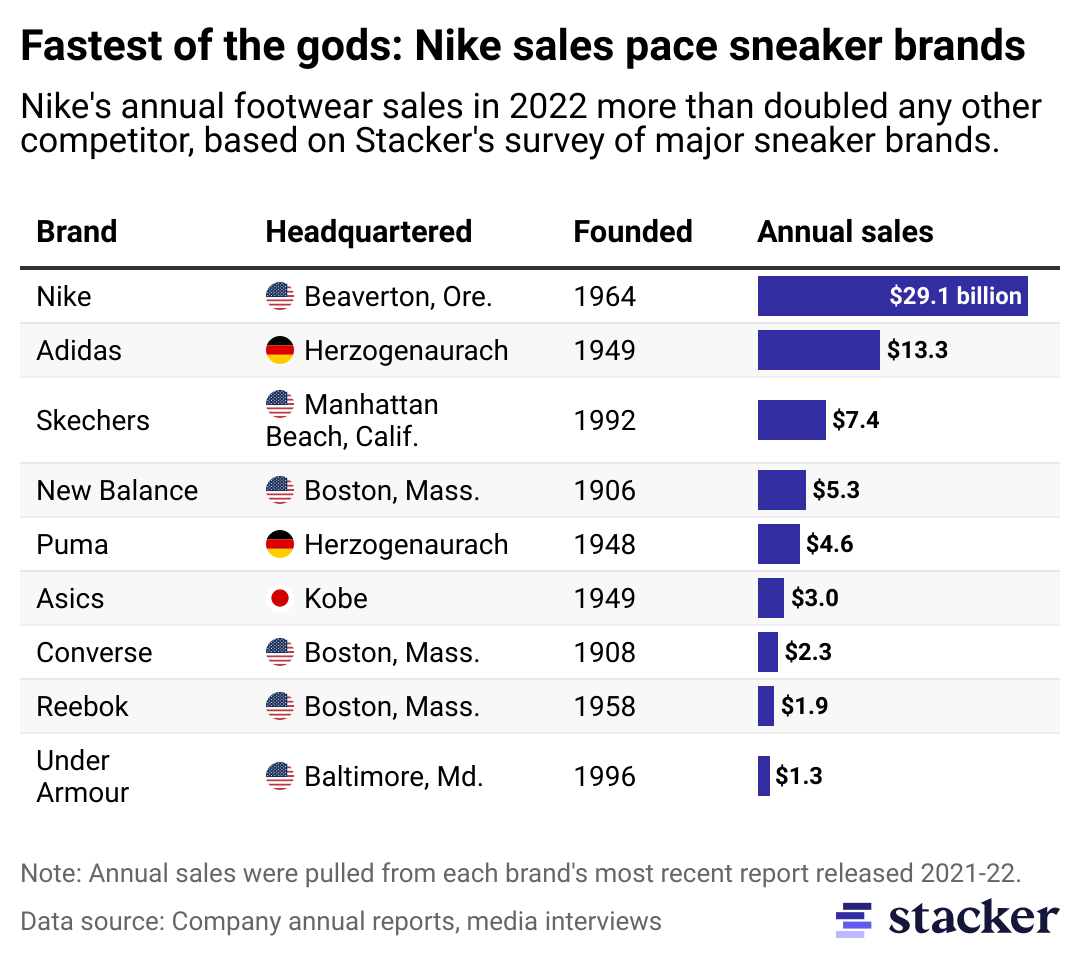

Nike’s dominance and the future of sneaker culture

Ask any sneakerhead about their most memorable footwear, and it’s almost always a Nike. For Ibgui, it was the Jordan 11 low citrus he finally bought in high school for around $150 on Melrose Avenue in LA. For legendary streetwear designer Jeff Staple, it was the Jordan IIIs he wore as a sixth grader in New Jersey. Serena Williams thinks the coolest pair of all time is the Nike Air Force 1.

When it comes to athletic shoe brands, Nike is undeniably at the top of the heap. The shoe giant has made many right moves since its inception in 1971—from signing Michael Jordan to its creative campaigns such as “Just Do It,” which has now become a rallying cry for more than just athletes.

However, Nike’s dominance doesn’t make the sneaker market less interesting, as Adidas continues to sprint behind it. In 2002, avant-garde fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto noticed men in their business suits wearing sneakers and approached Adidas with an industry-shocking collaboration (after being rebuffed by Nike), which is now celebrating 20 years. The three-striped shoe brand also worked with soon-to-be Moschino creative director Jeremy Scott on models that can now fetch up to $20,000 on the resale market.

Signature fashion houses eventually got into the game with a Louis Vuitton and Kanye collaboration in 2009 and Buscemi sneakers in 2013. It is worth noting that Gucci was the first luxury brand to release a shoe with its signature green and red stripes way back in 1984.

Adidas continues to recruit new sneakerheads. Many new recruits have discovered the brand through TikTok, the latest way shoe brands are reaching their young clients, said Gio Peluso, a salesperson at HypeLA. This year alone, Adidas saw three of its retro shoe styles—the Gazelle, Samba, and Campus 00s—blow up thanks to the TikTok hype and the influencers who build it.

Niche sneaker brands are popping up thanks to Instagram and the like. Studio Hagel by Mathieu Hagelaars, popular for its Makers Monday series on Instagram, got enough steam to launch its own experimental footwear brand—the kind that looks like it should be on “The Fifth Element.” Austin Babbitt, aka Asspizza, was a teenager with what Fader calls a “preternaturally strong command of social media” and now has an independent sneaker brand called 730 Footwear.

Sneakers have even made the move to the metaverse. In 2021, Fortnite fans could find Air Jordan IX Cool Grey shoes online before the shoe was released in stores. That same year, Staple, who helped design the Pigeon Nike SB Dunk Low, sold digital-only sneakers as NFTs through RTFKT Studios, priced at around $500.

Whether they slip on comfortably, snap heads on the street, or exist only in the digital world, sneakers are here to stay. No matter what, their value goes beyond their raw materials, like an amulet or totem we’ve imbued with special meaning. “Some sneakers are never just sneakers,” said Semmelhack. “They ultimately connect back to historic moments [and personal] memories.”

Data reporting by Jared Beilby. Story editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.