by Maya Pottiger

For the last 18 years, Youth Empowerment Solutions, or YES, has enabled kids in Michigan to make a difference in their community. The program, run out of the University of Michigan, was created in 2004 out of a need to improve public safety, and reduce crime and violence, especially youth violence.

“We said, ‘Let’s get the kids involved in the solution instead of just being the focus of the problem,’” says Dr. Marc Zimmerman, a professor at the University of Michigan School of Public Health and director of YES.

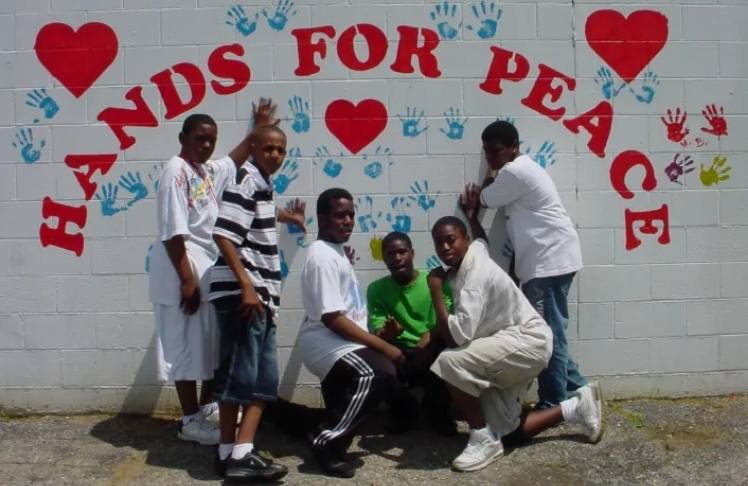

Through the after school program, kids develop, design, and enact community change projects, like murals and gardens. The program is taught through active learning and three key components: team building, community strengths and weaknesses, and community assets and liabilities.

In Philadelphia, the National Organization of Concerned Black Men program launched in 1975 as a way to slow the influence and spread of gang violence in the city. The organization now has more than 30 chapters across the country, and it provides educational leadership and mentoring services to students after school.

These organizations help underscore the importance of after school programs, especially for Black youth.

“It’s vitally important that we provide resources and positive programs and mentors for our young people to see … someone that looks like them exists in a certain profession,” says Dr. Karen McRae, CEO of CBM. “If you can see it, you can be it, but if you don’t see it, you don’t know it’s possible.”

After School Programs Provide Key Skills for Future Development

After school programs come in all shapes and sizes, meaning they can provide the opportunity for kids to develop any number of key life skills and lessons.

For one, the programs allow them to engage in positive behaviors with positive role models and positive peers, some of which could be a different group than who they interact with at school.

This means the kids are accounted for during “idle time,” or the time between when they get home from school and their parents get home from work, which is typically when they get in the most trouble, Zimmerman says. By filling the time with positive activities, they don’t have time to do “bad stuff” and are also engaging in a positive developmental aspect of human life.

“It’s a space where not only kids can feel safe and have fun and interact with their peers, so they’re building their social skills,” says Nikki Yamashiro, vice president of research at Afterschool Alliance, “but it’s a place that’s also providing academic enrichment.”

In terms of academic enrichment, they can be learning about STEM principles while doing a fun activity like gardening, or explore their passions in a low-stakes setting, allowing them to see new areas of interest and potentially discover career fields they hadn’t thought of before.

So the lack of access means lacking opportunities and experiences peers are getting.

“It’s missing out on an invaluable learning time where they could be finding new passions,” Yamashiro says, “figuring out what they want, the career path that they see themselves in, connecting with caring adults and mentors.”

Black Families have Faced Higher Rates of Unmet Demand Since 2004

A new report by Afterschool Alliance found that accessing after school programs is still a challenge for many families, specifically that for every child that does have a spot in an after school program, there are four more who don’t.

Black and Latino families cite the highest unmet demand for after school programs, according to the report. Among Latino families, 60% say they don’t have access to after school programs but would enroll their children if there were programs, followed by 54% of Black families.

This isn’t new. Historic data from Afterschool Alliance shows that Black families have faced high averages of unmet demand for after school programs since 2004, where unmet demand for Black families was 53% compared to the national average of 30%.

In every year measured — 2004, 2009, 2014, and 2020 — the unmet demand for Black families was consistently higher than the national average, with the biggest gaps being in 2004 and 2009, where there was a 23% percentage point difference. In more recent years, unmet demand for Black families has dropped while the national average has increased, balancing out to a 58% unmet demand for Black families in 2020 compared to 50% nationally.

There are both deep and surface-level explanations, Zimmerman says. The deeper explanation is the country’s history of structural racism that has kept resources from majority-Black and low-income schools.

On the surface-level, schools often need to write grants to find local foundations or federal dollars to fund these programs. It doesn’t seem like a big obstacle at first, but schools are already understaffed, so finding someone who is both qualified and has the time to complete the applications can be difficult.

“There’s just not the personnel to actually teach the program,” Zimmerman says. “Since COVID, that’s been for everybody, that’s not unique necessarily, but it’s exacerbated with the school issues that are going on.”

Black Families Experience High Barriers to Enroll in After School Programs

The unmet demand is largely because Black and Latino families face greater barriers to enrolling their children in programs compared to the average parent nationwide.

For Black families, the barriers are largely that the programs are inaccessible. Most commonly reported among Black adults was the programs not being in convenient locations (60%), followed by their children not having a safe way to go between the program and home (58%) and the program’s hours don’t meet the parents’ needs (57%).

“We’re seeing greater challenges when it comes to accessibility,” Yamashiro says, “whether that’s reporting that there isn’t a safe way for the child to get to some programs or the hours of operation don’t meet their needs.”

More than half of Black parents cited expense as a barrier, but it was not among the top three.

Some of these barriers are being addressed around the country, especially with the help of the American Rescue Plan, which helped fund a lot of school and summer programs.

In Arkansas, the ARP helped fund 44 after school, summer, and extended learning programs. In Illinois, a before and after school program jumped from serving 50 to 500 students, thanks to COVID relief funds. And Breakthrough Atlanta is receiving ARP funds across three years to help hire staff, feed students, and provide transportation for students in the program.

Enrollment is Down Among Black, Latino, and Low-Income Families

Though students have largely been back to school in-person, attendance for after school programs has not returned to pre-pandemic levels. The decline is visible across demographics but higher among low-income families, with attendance dropping from 11% in 2020 to 8% in 2022.

The decline is also higher among Black children compared to white and Latino children, with Black children seeing a five percentage point decline compared to only three percentage points among white children and one point among Latino children.

The problem can stem from both sides. For one, people still aren’t back to their normal routines. And on the other side, there are staffing and funding issues keeping programs limited in how many kids they can serve. At CBM, McRae says they’re working on recruiting more mentors in order to meet the need.

“They want to serve more students, and if they were able to step up their normal levels, they would be able to,” Yamashiro says.