“Katrina: 20 Years Later” is Word In Black’s series on Hurricane Katrina’s enduring impact on New Orleans, and how Black folks from the Big Easy navigate recovery, resilience, and justice.

Twenty years after Hurricane Katrina drowned New Orleans, the waterlines from the once-in-a-generation storm are still visible. Not on the shotgun houses that were gutted, or bulldozed, nor on the gleaming, glass-and-steel high-rise towers looming over downtown.

The floodlines linger in numbers: census data showing a declining Black population; skyrocketing rents driving out the working class; vacant lots dotting neighborhoods that never came back — and the families who never did either.

Two decades after the costliest natural disaster in United States history slammed into the Gulf Coast — killing some 1,400 people, with hundreds still unaccounted for — the official story of New Orleans is one of resilience. Its boosters say Crescent City has been reborn, with booming tourism, bustling restaurants, and polished infrastructure.

But beneath the marketing slogans, the football championship games in the Superdome and Mardi Gras revelry, Katrina’s scars remain. The Big Easy, experts say, is smaller, whiter, and less affordable. Poverty is as entrenched as ever, and the gulf between the haves and have-nots has widened.

A Changed City

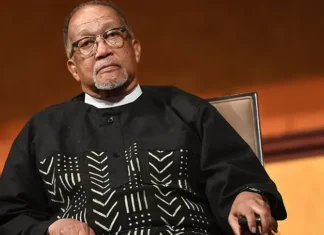

The storm “definitely shifted the culture of the city,” says Allan Hyde, a sociologist at Georgia Institute of Technology. Hyde studied post-Katrina demographic changes in New Orleans and how its Black evacuees ended up scattered across the Sun Belt, settling for good in places like Houston, Atlanta, and Dallas.

“Some folks couldn’t afford to move back, even if they wanted to, because things got so expensive” once the city, the government, and homeowners began cleanups and renovations, Hyde says. “Some people were reluctant to go back. Maybe their house wasn’t destroyed, but they couldn’t work,” because the storm shut down or washed away their employer.

Although many yearned to return to The Big Easy, Hyde says, staying put was a practical decision that further exposed the city’s inequality.

“You’re still going to have bills that you have to pay, but you still need a job,” Hyde says. “And so many people were working in the service industry, especially around tourism. So food services, bars, restaurants — a lot of that was canceled for a while as the city got back on its feet.”

After a year or two in another city, “you start to develop relationships, build a life there,” Hyde says. “And some people are less inclined to go back.”

A Disaster of Inequality

Hurricane Katrina was a Category 3 storm that became a Category 5 disaster. The levees crumbled, and 80% of the city was submerged. But the storm surge did not hit all New Orleanians equally. It swept hardest through the poorest, Blackest neighborhoods, revealing the fault lines of segregation and disinvestment.

The Lower Ninth Ward, a historically Black neighborhood hemmed in by industrial canals, became a national symbol: houses splintered, lives scattered, entire blocks emptied. Families with cars and cash got out. Those without were left clinging to rooftops or herded into the Superdome.

What is the history of exclusion and marginalization in that city. Who is most at risk?Allan Hyde, Georgia Institute of Technology

Hyde notes the seeds of the suffering had been sown long before 2005.

New Orleans’ history of segregation and disinvestment in places like the Lower Ninth had already weakened Black neighborhoods. Redlining pushed the Black middle class to the suburbs in search of better opportunities, taking with them businesses, churches, and institutions that anchored community life.

What remained, Hyde says, were under-resourced neighborhoods with fewer jobs, rising crime, declining housing demand, and falling property values — leaving them especially vulnerable when the storm hit.

“People that rent — they’re going to be most disadvantaged,” he says. “So I think when it comes to understanding how disasters will affect cities, it’s important to think about what is the history of exclusion and marginalization in that city. Who is most at risk?”

A Recovery That Remade, Not Rebuilt

The water receded, but the city that emerged was not the same. The recovery promised to rebuild. Instead, it remade.

More than 134,000 occupied homes — about 70% of the city’s housing stock — were damaged or destroyed. Public housing complexes, once home to thousands of poor and working-class Black families, were demolished, replaced with mixed-income developments that offered fewer units and higher rents.

At the same time, developers and out-of-town buyers scooped up ruined properties for pennies, flipping them into trendy rentals or second homes. For evacuees trying to return, the math rarely worked.

Gentrification and Displacement

By 2010, the city’s Black population had fallen by nearly 100,000 people compared to before the storm. Meanwhile, living in New Orleans became more expensive. Between 2004 and 2013, median rents jumped 33%, far outpacing income growth. Affordable apartments vanished, and the neighborhoods that once anchored Black culture — Treme, Central City, the Lower Ninth — became prime territory for gentrification.

The Inevitable Next Storm

Katrina did not just break the levees. It redrew the map of who belongs in New Orleans — and who does not. The storm was a natural disaster. The recovery was man-made. And Hyde doesn’t think Katrina will be the last storm to transform the city.

As climate change makes extreme weather events more deadly, and as Trump cuts government climate research and talks of eliminating FEMA, “it puts us at risk, and puts particularly communities of color at risk,” he says. “It’s just not seen as a priority, because it’s talking about race, when some people are uncomfortable talking about race in 2025.”