By Linda Villarosa

By Linda Villarosa

BAI Contributor

Throughout AIDS 2016, whispers that global funds to fight HIV/AIDS have begun to dry up have turned to shouts. In the crowded hallways of the International Convention Center, on panels, plenaries and even t-shirts, everybody seems to be worried that The Global Fund to Fight HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria won’t be fully funded and international dollars are fading away. In fact, organizers of Monday’s march through Durban said they created their event to bring attention to the “massive disconnect” between the promises to end HIV/AIDS by 2030 and the lack of funding to actually make it happen.

But is this a Chicken Little tactic to create the appearance of need? Or is it real? According to a new report, yes, it’s real.

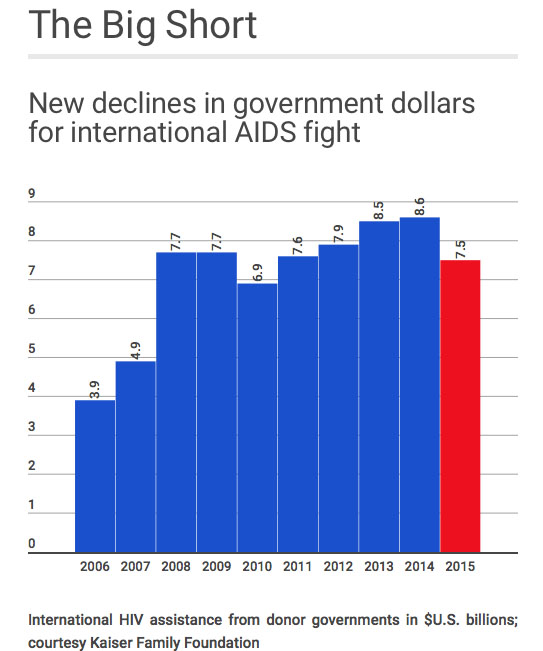

Donor government funding to support HIV efforts in low- and middle-income countries fell for the first time in five years in 2015, according to data gathered and analyzed jointly by the Kaiser Family Foundation and UNAIDS. In U.S. currency, over $1 billion dried up; AIDS money dropped from $8.6 billion in 2014 to $7.5 billion in 2015, a 13 percent decline.

Money matters. With the goal of ending AIDS by 2030, the movement has reached a critical moment. As death rates have plummeted, more and more people require life-saving treatment. In essence, the epidemic has become a “victim” of its own success. In 2000 when the AIDS conference was first held in Durban, 1.5 million people died from AIDS around the world; that number dropped to about 1 million in 2015. Sixteen years ago, 770,000 people living with the virus had access to treatment, compared to 17 million currently.

UNAIDS estimates that to reach its “fast track” goals and end AIDS in the next 14 years requires an increase of at least $7.2 billion by 2020. “Our progress is incredibly fragile,” said Michel Sidibe, executive director of UNAIDS. “If we do not act now, we risk resurgence and resistance.”

The United States contributes the lion’s share to global funding—66 percent—and American dollars decreased from $5.6 billion in 2014 to $5 billion in 2015. The vast majority of our money funds specific projects and programs, with an additional 14 percent given to The Global Fund. (Overall contributions to the Global Fund dropped by $305 million.) The U.K. follows the U.S. in donations, supplying 13 percent of AIDS money. With a nod to the disruption occurring in that country, one conference attendee carried a sign that read England—Don’t “Brexit” the AIDS Response.

Funding for HIV declined for 13 of 14 donor governments assessed in the analysis, in part because of a technical reason: The U.S. dollar became stronger, resulting in the depreciation of most other donor currencies. Even some of the drop in funding from the U.S. itself can be explained away on paper. The U.S. pushed some of its dollars into the 2016 spread sheet to pay for the new DREAMS project aimed at attacking HIV infections among girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa and to expand male circumcision services in many of the same countries.

Still, in the words of Jen Kates, one of the authors of the report, “it’s a real decline.”

In our increasingly complicated and unstable world, a tangle of reasons explain the funding drop off. “We know that governments are facing fiscal austerity measures,” explained Kates, a Kaiser Family Foundation vice president. “We also know that they are faced with competing demands, including refugee and humanitarian emergencies that are affecting their budgets.”

No matter the explanations, activists are worried—and angry. “We can’t be silent in the face of hypocrisy and broken promises,” said Nkhensani Mavasa, chair of South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign, during the AIDS 2016 opening ceremony. “Governments are refusing to deliver funding increases and this is unacceptable.”

More bluntly, she added: “When your house is burning and your family is inside, you don’t beg quietly but you shout and you scream. Our house is still burning.”