This article is one of a series of articles produced by Word in Black through support provided by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Word In Black is a collaborative of 10 Black-owned media outlets across the country.

Dr. Michelle Rankins has hosted African American Read-Ins for 23 years.

Sometimes they’re held at her church or library, and, one time, in her own home. They can come in the form of a poetry reading or open mic. Another time, everyone brought a book by their favorite Black author and discussed why they liked it.

“The whole idea is to utilize Black History Month as a vehicle in which we bring forth the celebration of Black authors,” says Rankins, an assistant professor of English at Cuyahoga Community College. “As long as you are celebrating African-American authors — it could be traditional authors, new authors, it’s really up to you.”

Rankins brought the Read-In to her campus in 2015 to improve student engagement. Since it started, she has seen more students get involved, share their stories, and ensure their voices are heard.

Down in Atlanta, Dr. Charity Gordon organizes a Read-In at Georgia State University, where she is a clinical professor and serves as the director of the Urban Literacy Collaborative and Clinic.

Gordon’s Read-In features events throughout the day, with a live band, giveaways, breakout sessions, trivia, and readings by local authors.

“It’s centered around all the Black literary traditions that are pivotal in our community, that are important in our community, that make us who we are,” Gordon says.

The Beginning

The AARI was established in 1990 by the Black Caucus of the National Council of Teachers of English, of which Rankins and Gordon are both members. The goal was to make literacy a significant part of Black History Month.

Since its inaugural year, the program has reached over six million participants worldwide.

“It has grown to be this global initiative that people have taken up and are excited about,” Gordon says.

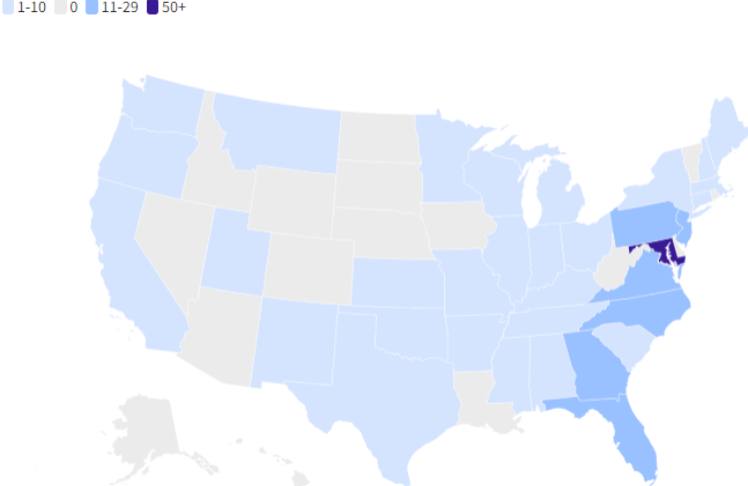

In 2022, about 213,000 people participated in the African American Read-In around the country. Over half of all U.S. states participated, with Maryland in the lead, hosting a whopping 83 Read-Ins.

The majority of states held African American Read-Ins in 2022, with Maryland leading at 83 participating locations.

But, even though the event is growing, it isn’t being met without resistance.

Keep Telling Stories

As the history of Black Americans in this country continues to experience erasure in school curriculums across the nation, the African American Read-In is more important than ever this year.

“We’re seeing the censorship, not just in K-12, but also filtering into [university] spaces. The restrictions of not wanting to tell African-American stories, or stories of Black Americans, or what have you,” Rankins says. “That’s why programs like the Read-In are so important because we’re celebrating in public spaces: We are celebrating the works of African-American authors and poets and other creatives.”

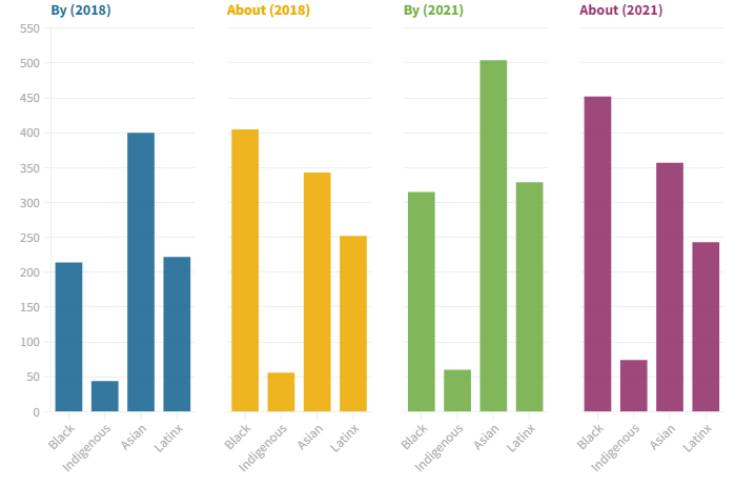

The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cooperative Children’s Book Center has been tracking books published by diverse authors since 2018. Since then, the number of children’s books by and about Black people has steadily risen, from 17% in 2018 to 22% in 2021, according to the most recent data available.

The number of books published by and about Black people have been steadily rising since 2018

Though her first event had public support from Georgia State, and excitement surrounding it, Gordon says the university isn’t as supportive as it once was.

“We are having to do a lot of things on our own,” Gordon says.

In April 2022, Georgia joined other Republican-led states in banning schools from teaching “divisive” concepts about race and racism — namely critical race theory. This means that, though Georgia State is supporting the event on paper, it seems like the university would rather not attach its likeness to the literacy event this year.

Although some educators feel the administration’s stance puts pressure on them to be quiet, Gordon says, she feels the opposite. Instead, she feels more driven and values the importance of the Read-In even more.

“We have to keep telling the stories where we have the opportunity, and understanding that when we are telling stories, we are participating in a centuries-old tradition of the oral tradition,” Rankins says. “Books themselves are critical and important, and I don’t think they will ever go away.”

Full Circle Moments

One of Rankins’ favorite things about the Read-Ins is that you never know what will happen or what special moment you’ll take away from it.

For her, a standout memory is from her 2016 Read-In that gave Black men a space to read and discuss Black authors. She said, after discussing the literature, the men began reflecting on their relationships with their sons and how it felt to be a Black man in America at the time.

“It just became this really wonderful storytelling session,” Rankins remembers.

But what truly stuck out to her was that, after the event, one of her students asked to check those same books out of the library.

“Moments like that, where your students are really engaged and ask for a book afterwards — I mean, it doesn’t get any better than that,” Rankins says.

When Gordon was a Ph.D. student studying language and literacy education, she said she was still learning so much about her own culture that she’d often leave class and feel like the world looked new. It compelled her to make sure the generation behind her was not only aware of their culture’s literary traditions and histories but proud of them — something that didn’t happen for Gordon until she was a Ph.D. student.

“We wanted to create a space where the children in our community felt affirmed, or they understood their worth or value, or they understood where they came from,” Gordon says.

“They understood that these literary traditions that we are always engaged in are worthy and are valuable.”

The full circle moment came for her in 2016 after a Black third-grader read “I’m a Pretty Little Black Girl” at an event. Her mother reached out to Gordon later to say that her daughter was being bullied at school over her appearance. And when her mom asked what she thought at that moment, her daughter replied, “I don’t care because I’m a pretty little Black girl” — a reference to the book she read at Gordon’s event.

“That was exactly the goal that I wanted. I wanted them to feel affirmed and feel confident in their own skin and who they are,” Gordon says. “So that was the goal. And that’s one of the outcomes.”