Bettmann // Getty Images

Written by Abby Monteil

United States currency today shows an extremely limited sample of the American people, traditionally depicting a static set of Founding Fathers, presidents, national memorials, and government buildings. On the other hand, women and people of color have been largely left off of the dollars and cents until very recently.

This reality has cultural implications, since who is chosen to be put on the currency sends a message about which figures are respected and remembered for their contributions, as Smithsonian curator Ellen Feingold pointed out in an essay written for Politico.

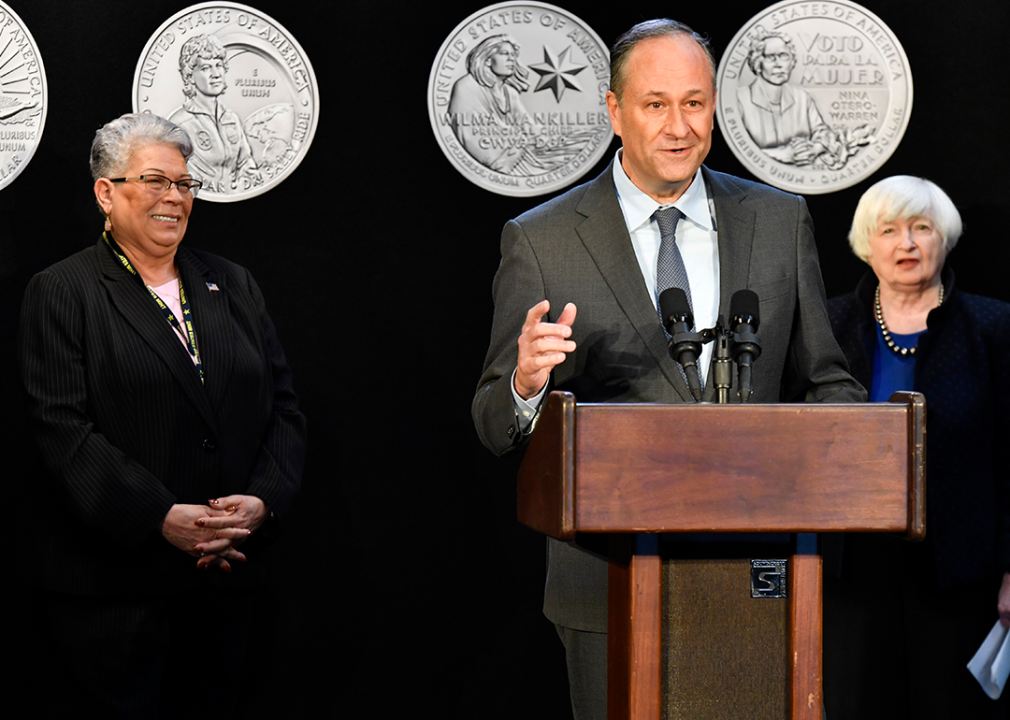

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which gave white women the right to vote, the U.S. Mint launched the American Women Quarters Program. The program celebrates the contributions of women in the U.S. by featuring them on quarters. It began in 2022 and will come to an end in 2025. Below, the 20 honorees as of January 2024 are listed in order of issuance, including the 10 released from 2022 and 2023, as well as the 10 set to come out in 2024 and 2025. But who are these women on your quarters?

Stacker explored the fascinating lives and achievements of the 20 remarkable women celebrated by the American Women Quarters Program. However, while introducing women onto U.S. currency is a step toward recognizing women in U.S. history, it’s by no means a pioneering one. Many other countries have long had women figures on their currency, from Australia to Mexico. It’s also worth recognizing that the U.S. Mint adheres to a binary understanding of sex and gender, making the proper inclusion of gender-expansive people difficult.

It remains to be seen if the U.S. Mint will meet demands to overhaul its currency further to celebrate underrecognized historical figures. In the meantime, meet the women on your quarters—from Maya Angelou to Maria Tallchief—and learn why they matter.

Larry Morris / The Washington Post via Getty Images

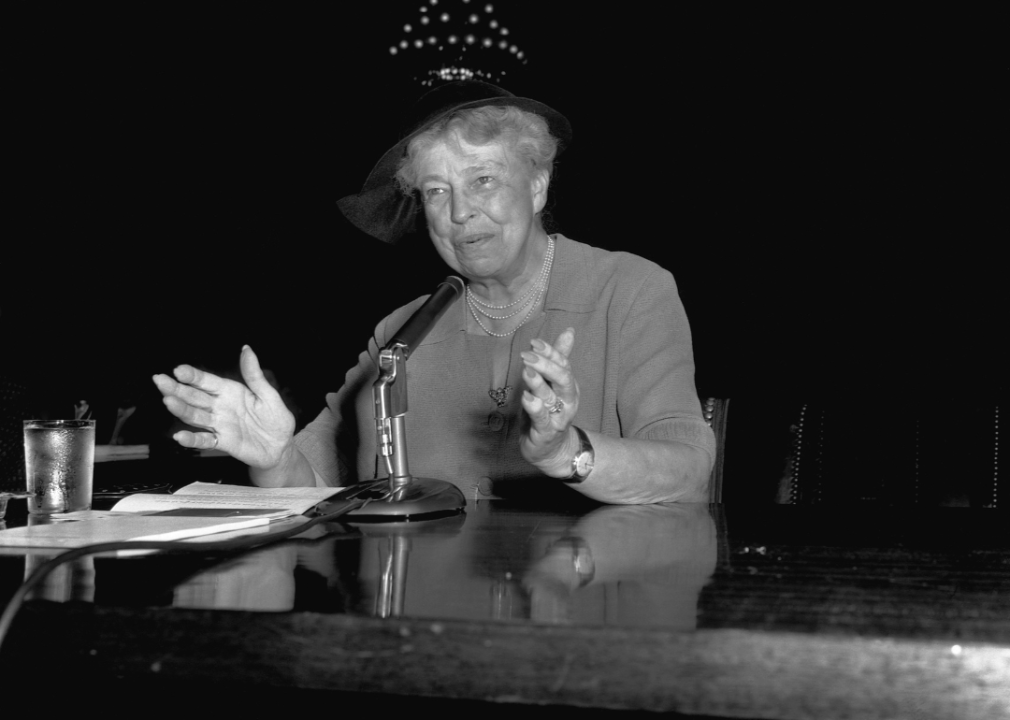

Maya Angelou

Writer, performer, and activist Maya Angelou began the U.S. Mint’s roster and made history in 2022 as the first Black woman to appear on a U.S. quarter. She rose to prominence after publishing her classic 1969 autobiography “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.”

She published over 30 other works, including memorable poems like “Still I Rise” and “On the Pulse of Morning,” reading the latter at President Bill Clinton’s 1992 inauguration. Angelou is also remembered for her civil rights work alongside Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and she worked on the Southern Christian Leadership Conference staff. In 2010, President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Sally Ride

A pioneer in space exploration, Sally Ride became the first American woman to walk in space, as well as the first to make two trips to space. Ride served as a mission specialist during the 1983 Space Shuttle Challenger STS-7 mission, in which she helped retrieve two communications satellites and conducted scientific experiments.

In 1984, she completed her second mission aboard the Challenger, using the shuttle’s robotic arm to release the Earth Radiation Budget Satellite. After resigning from NASA in 1987, she focused on breaking down barriers for young women in STEM with her own company, Sally Ride Science. The company created immersive educational science, technology, engineering, and math programs for elementary and middle school students, encouraging more women to reach for the stars.

Peter Turnley // Getty Images

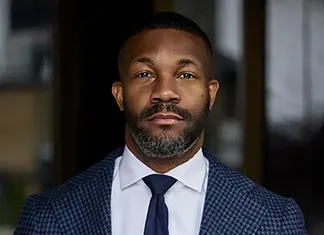

Wilma Mankiller

In 1985, Wilma Mankiller became the first woman principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. Before her election, she founded the Cherokee Nation’s Community Development Department, overseeing the creation of community water systems and the restoration of houses.

Mankiller tripled membership in the Cherokee Nation during her time as chief, saw lowered infant mortality rates, and doubled Cherokee employment. She also worked with the federal government to pioneer a self-government agreement between the Cherokee Nation and the Environmental Protection Agency. Mankiller was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993 and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998.

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

Nina Otero-Warren

Nina Otero-Warren was the first Hispanic woman to run for U.S. Congress and a leader of New Mexico’s women’s suffrage movement. In 1918, as the first female superintendent of public schools in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Otero-Warren emphasized the importance of using Spanish to make the suffrage movement accessible to Hispanic women.

In her education work, she promoted bicultural education, citing the importance of preserving Hispanic and Native American cultures within New Mexico. Her legacy persists today, as activists work to offer ballots in more languages and raise awareness of the growing legislation spreading across the nation that attempts to limit teaching about race, racism, and multicultural history in schools.

John Kobal Foundation // Getty Images

Anna May Wong

Anna May Wong became the first Asian American to appear on U.S. currency thanks to the quarters program. She was Hollywood’s first Asian American movie star, appearing in silent films, theater productions, and on television. Wong dealt with racism and harassment throughout her Hollywood career, eventually prompting her to go to Europe and star in several English, German, and French films during the late 1920s.

Wong’s legacy remains salient today, as the #OscarsSoWhite and #TimesUp movements advocate for more conscious, authentic diversity in film and urge accountability for perpetrating gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment or assault in the workplace and beyond.

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

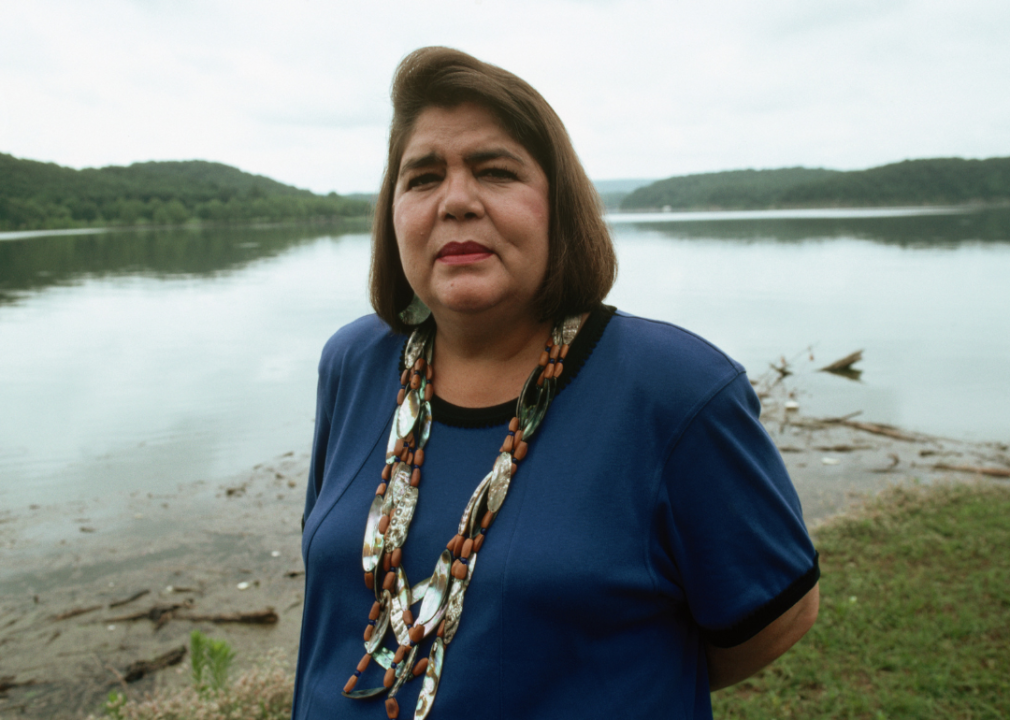

Bessie Coleman

A talented pilot, Bessie Coleman also made history as the first African American and first Native American woman pilot and the first African American to earn an international pilot’s license. After being refused admission into U.S. flying schools, Coleman traveled to France and eventually received her international pilot’s license in 1921 from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

She became known for her daring feats at air shows, performing loop the loops and figure eights. Coleman toured the U.S. as her fame grew, giving flight lessons and encouraging young African Americans and women to pursue aviation. Her legacy remains an important example, given the meager 9.5% of U.S. pilots who are women today, according to 2022 Federal Aviation Administration data.

Jason Connolly-Pool // Getty Images

Edith Kanakaʻole

Throughout her life, Hawaiian composer, chanter, educator, and Kumu Hula Edith Kanakaʻole was dedicated to celebrating and promoting the preservation of Native Hawaiian culture. Kanakaʻole did this by composing Hawaiian chants known as “oli,” choreographing hula dances, and teaching these practices to others. She also helped create the first Hawaiian language program for public school students.

In the 1970s, she designed and taught college courses on undertaught subjects like Hawaiian chant and mythology, ethnobotany, and Polynesian history. During a time when the Hawaiian language was banned in Hawaiian schools, Kanakaʻole’s efforts were ahead of her time.

Bettmann // Getty Images

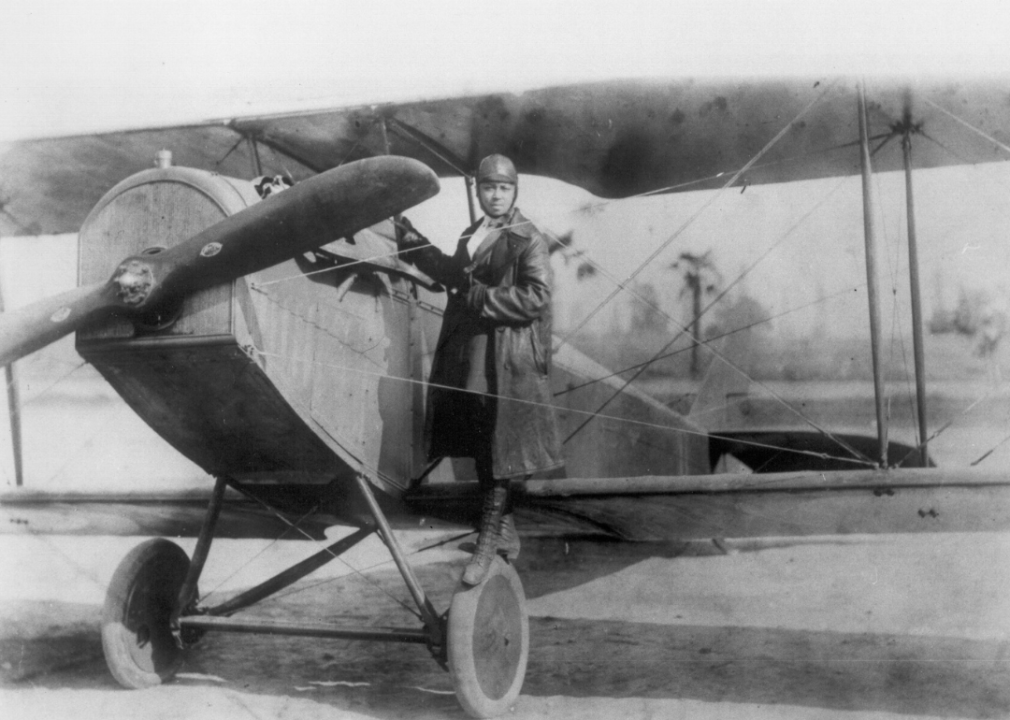

Eleanor Roosevelt

Eleanor Roosevelt held many titles: first lady, writer, and chairperson of the United Nations Human Rights Commission, just to name a few. Roosevelt became active in politics in the 1920s, promoting women’s political engagement through organizations like the Women’s Trade Union League and the League of Women Voters.

As first lady, she was known for her hands-on approach, visiting relief projects nationwide to lend her support. She remained politically active later in life, notably when former President Harry Truman appointed her to the United Nations. Roosevelt worked on drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which the U.N. General Assembly adopted in 1948.

Jason Connolly-Pool // Getty Images

Jovita Idar

Mexican American journalist, activist, teacher, and suffragist Jovita Idár used her writing and organizing efforts to fight for a better future for her fellow Latino Americans. Idár was exposed to the power of journalism from a young age; her parents ran the progressive, Spanish-language newspaper La Crónica, which exposed injustices toward Mexican Texans in the early 20th century. This encouraged her to pursue activism.

She helped organize the First Mexicanist Congress in 1911, which galvanized the Mexican American civil rights movement. She also founded the League of Mexican Women—one of the first Latina feminist organizations—and became its first president. Idár was passionate about education, launching El Etudiante, a weekly bilingual education newspaper for teachers, encouraging them to help bilingual students preserve their cultures. Idár used journalism to advocate for Latino Americans in several other publications, including El Progreso, El Eco del Golfo, and La Luz.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Maria Tallchief

Part of the Osage Tribe, Maria Tallchief is widely recognized as America’s first prima ballerina. Tallchief danced and worked for prestigious companies like the New York City Ballet throughout her career. Even as she gained acclaim, she refused to erase her heritage, opting to keep the Tallchief name rather than following the trend of adopting a Russian-sounding name to blend into the ballet world.

After retiring from dancing full-time, Tallchief sought to empower Native Americans by speaking to them and others about Native arts and education. She also helped raise funds for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Tallchief died in 2013, but her legacy continues to inspire ballet dancers of color—particularly Indigenous dancers—in the U.S. However, the art form remains predominantly white and is often unwelcoming to ballerinas of color.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Patsy Takemoto Mink

Patsy Takemoto Mink made history as the first woman of color elected to the House of Representatives, the first Asian American congresswoman, and the first Asian American to run for president of the U.S.

Born in Hawaii, Mink’s career took off when she was elected to the House of Representatives in 1964. Throughout her time in politics, she championed education and women’s issues, most notably pioneering the passage of the Women’s Educational Equity Act, which provided $30 million per year in educational funds to promote gender equality and job opportunities for women upon its enactment in 1974.

Mink was also one of the key authors and sponsors of Title IX, which prohibits sex-based discrimination in education programs. She ran in the Democratic presidential primary in 1971, basing her campaign on her “humanism” and anti-war activism.

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Mary Edwards Walker

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker remains the only woman in U.S. history to receive the Medal of Honor. During the Civil War, Walker became the first woman Army surgeon for the Union army. Working in the face of wartime danger and rampant sexism toward women doctors at the time, she often crossed enemy lines to deliver medical care. In 1864, she was captured and held prisoner for four months by the Confederate Army as a spy.

Beyond her medical prowess, Walker was a strong proponent of women’s rights, testifying in front of the House of Representatives to support women’s suffrage in 1912 and 1914. The activist also bucked gender conventions of the time, regularly wearing pants and advocating for “dress reform” throughout her life. Her refusal to conform to gender norms resulted in her arrest in New Orleans in 1870 for wearing masculine clothes.

Bettmann // Getty Images

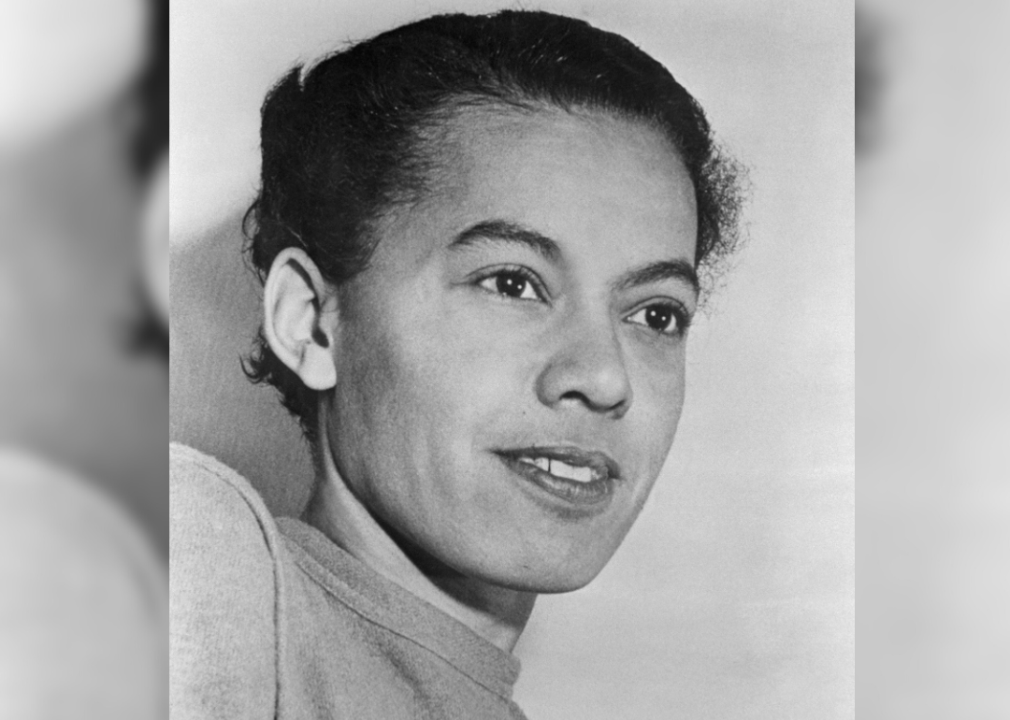

Pauli Murray

An undersung figure in the Civil Rights Movement, Pauli Murray was nevertheless a highly influential activist, author, and legal scholar. They broke barriers throughout their lifetime, co-founding the National Organization for Women in 1966 and writing the book “States’ Laws on Race and Color,” which Thurgood Marshall touted as “the bible” of the Civil Rights Movement. It often is cited as the foundation for the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, in which the court ruled segregation unconstitutional. Additionally, Murray became the first Black American to receive a Juris Doctor from Yale Law School in 1965.

While Murray was recognized as part of the U.S. Mint’s American Women Quarters program, it’s important to note that they were gender-nonconforming and self-identified as a “he/she personality.” Because language for their gender identity did not really exist during their lifetime, it is impossible to know how Murray would have wanted to be described using today’s language.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Zitkala-Sa

Writer and activist Zitkála-Šá, also known as “Red Bird,” used her artistic talents to advocate for the preservation of Native American culture, as well as improved health care, legal and voting rights, and education for Native Americans.

A member of the Yankton Sioux tribe, Zitkála-Šá was influenced at an early age by her experiences at a residential Quaker school designed to forcibly assimilate Native American children into white European culture and religion. As an adult, she published work about Dakota history and culture and sought to humanize her people at a time when Native Americans were often erased and cast as “savages.”

Meanwhile, Zitkála-Šá’s advocacy for Indigenous people to receive U.S. citizenship played a key role in the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which endowed full citizenship rights to all Native Americans. She also worked hard to secure suffrage for Indigenous people, urging white women to use their newly achieved right to vote to advocate for the same rights for Native Americans.

Frans Schellekens/Redferns // Getty Images

Celia Cruz

Widely recognized as the “Queen of Salsa,” Cuban American singer Celia Cruz played a major role in developing the new sound of the genre. Drawing on her Afro-Cuban heritage to shape and popularize salsa as it is known today, Cruz rose to stardom as part of the popular Cuban orchestra La Sonora Matancera. After the orchestra was exiled to the U.S. following the Cuban Revolution in the 1950s, she became a fixture of the New York City salsa scene.

During her career, Cruz recorded over 80 albums, winning four Grammy Awards and three Latin Grammys. She was known for her trademark interjection, “¡Azúcar!,” which held deeper meaning as a reference to the enslavement of Africans on Cuban sugar plantations.

Chicago History Museum // Getty Images

Ida B. Wells

Black investigative journalist and activist Ida B. Wells played a key role in documenting and speaking out against the lynching of Black people. Following the lynching of a friend and his two associates, Wells published a series of articles investigating the crime. She eventually brought her anti-lynching campaign to the White House, speaking to President William McKinley in 1898.

She also became one of the few Black women in the country at the time to own and edit a newspaper, the Memphis-based publication Free Speech. Although she was not credited as an official founder, Wells helped start the NAACP and other civil rights organizations, such as the National Association of Colored Women’s Club. In 2020, Wells received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for her vital reporting work.

Bettmann // Getty Images

Juliette Gordon Low

Known to some as “Daisy,” Juliette Gordon Low founded Girl Scouts of the United States of America in 1912. Low was inspired to start the organization after meeting Boy Scouts founder Sir Robert Baden-Powell in England and learning more about the country’s Girl Guides program. Low’s Girl Scouts set itself apart by teaching young girls leadership and outdoor skills and preparing them for homemaker roles.

From its inception, the Girl Scouts was open to girls with disabilities, immigrants, and girls from various ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Low herself was a hard-of-hearing person, and historians have speculated that she may have also had a learning disability. As of 2017, Girl Scouts is the largest organization for girls, totaling over 50 million members throughout its history.

Linda Davidson/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Vera Rubin

Trailblazing astrophysicist Vera Rubin is regarded as the “mother of dark matter.” Despite the lack of representation and opportunities for women in science, technology, engineering, and math in the mid-20th century, she collaborated with fellow astronomer and instrument designer Kent Ford to analyze over 60 galaxies.

During her research on galaxy rotation in the 1970s, Rubin discovered clear evidence that convinced astronomers around the world of the existence of dark matter—a form of matter composed of particles that don’t absorb, reflect, or emit light and can’t be detected through electromagnetic radiation. Her research affirmed the theory that dark matter is abundant throughout stars and galaxies. In 1993, Rubin was awarded the National Medal of Science for her contributions.

Jason Connolly-Pool // Getty Images

Stacey Park Milbern

Queer Korean American disability justice activist Stacey Park Milbern advocated for the inclusion of people of color and transgender and gender-nonconforming people in the disability justice movement. Following her move to the San Francisco Bay Area, a then-24-year-old Milbern founded the Disability Justice Culture Club as a place where queer disabled people of color could organize and find community. In 2014, President Barack Obama appointed her to the President’s Committee for People with Intellectual Disabilities.

The activist went on to co-produce the impact campaign for the Netflix documentary “Crip Camp,” which tells the story of how a ’70s New York summer camp helped launch the disability rights movement. Although Milbern died in 2020 at 33 from surgery complications, she forged a legacy of championing intersectional disability justice across the U.S.

Bettmann // Getty Images

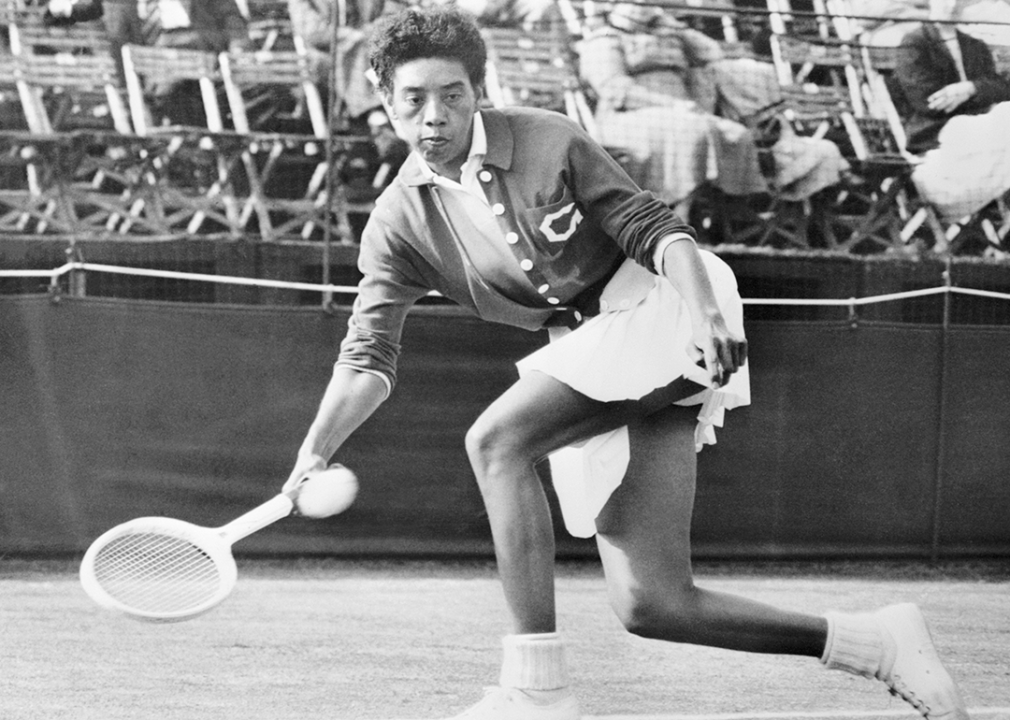

Althea Gibson

During an era when tennis was still segregated and overwhelmingly considered a “white” sport, Althea Gibson shattered barriers. The prodigious athlete became the first Black tennis player to compete in the U.S. National Championships, now known as the U.S. Open, in 1950. She later won the event in both 1957 and 1958.

During that same two-year period, Gibson won back-to-back Wimbledon championships, where she was the first Black player to win, predating Arthur Ashe’s historic win by over a decade. However, her achievements weren’t limited to tennis: In 1967, she became the first Black American woman to compete on the Ladies Professional Golf Association tour.

Story editing by Eliza Siegel. Copy editing by Lois Hince.