By Tierney Sneed, CNN

(CNN) — If the Supreme Court issues a ruling that would allow states to ban abortion, as is expected in the coming days, such a decision would raise new questions about how authorities would enforce such bans and whether the anti-abortion movement would stick to its public emphasis on protecting abortion-seekers themselves from prosecution.

What has been the pattern abroad in countries that ban abortion, along with United States’ own experience before Roe, previews a complicated and unequal enforcement landscape.

For years as they fought to overturn Roe v. Wade, leaders of the anti-abortion movement have stressed that prosecutions should be focused on abortion providers and others who facilitate the procedure, rather than the person seeking it. But the movement’s critics point to examples of when the criminal justice system has already — with Roe still on the books — been turned on women whose pregnancies have been purposely or inadvertently terminated.

In one 2018 case, for instance, a Mississippi woman who experienced a stillbirth was accused of second degree murder after authorities obtained her phone data and found she had searched for abortion pills. (The case was later dropped after prosecutors took a closer look at the evidence, including the use of a scientifically questionable test to supposedly determine whether the fetus had been born alive.)

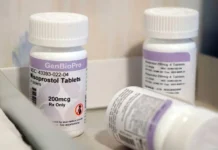

One major challenge abortion foes will be facing if Roe falls is the growing use of medication abortion, which allow for women to manage their own abortions in two-pill regimen without the help of the kind of physician that would conventionally be prosecuted under an abortion ban.

Because pregnancies that end in a natural miscarriage are often indistinguishable from those terminated with a pill, it’s possible that women’s private data and the information they share with their medical staff will be weaponized by prosecutors. Even if the woman herself is not criminally liable, she may still be dragged through the law enforcement process as part of prosecutors’ efforts to investigate whether her pregnancy was illegally terminated.

“What I found in my research is that women were indeed punished, even if, you know, almost none of them are prosecuted and incarcerated for having an abortion,” said Leslie Reagan, a history professor at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and author of “When Abortion Was a Crime.” “That is through the methods of enforcement: interrogating women who were seeking emergency services after having an abortion or trying to induce their own.”

How suspicions of abortions could be investigated

Whether to bring a case under a state abortion restriction will be a decision ultimately for the local prosecutor, and the promise of some district attorneys in Democratic-leaning localities to not prosecute abortion crimes has prompted red states to explore other mechanisms to carry out bans.

But in places where law enforcement officials seek to enforce abortion prohibitions, medical staff who provide treatment to women whose pregnancies have ended could also end up being a source of information for law enforcement officers.

In El Salvador, a country with an extremely aggressive approach to carrying out its ban on abortion, government officials are dispatched to hospitals to stress to medical staff their obligation to report suspicions that a patient has intentionally ended her pregnancy, according to Michelle Oberman, a Santa Clara University School of Law professor and author of “Her Body, Our Laws: On the Frontlines of the Abortion War from El Salvador to Oklahoma.”

Doctors are told that “if they don’t report those women, they themselves can be subject to fines and other penalties,” Oberman said.

In the United States’ pre-Roe era, women who sought medical care after abortions faced interrogations, Reagan said, including threats that “we won’t provide medical, the medical care that you urgently, urgently need” unless they cooperated with the investigations.

Even now, medical care that women receive for pregnancies that have been ended can lead to law enforcement getting involved, according to Dana Sussman, the acting executive director of National Advocates for Pregnant Women. Sussman’s organization provides defense attorneys and other resources for people facing charges or investigations related to pregnancy and its outcomes. The organization has documented 1,700 arrests, prosecutions, detentions, or forced medical interventions between 1973 and 2020 on women related to pregnancy or pregnancy outcomes, though the majority of those cases don’t involve a pregnancy loss or abortion.

If Roe is reversed, Sussman said, “I think that there will potentially be a lot more collaboration between health care providers and the police.”

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act — a 1996 law also known as HIPAA that sets privacy standards for protecting patients’ personal medical information — has exceptions for law enforcement purposes, Sussman noted. “As we expand the ways in which criminal law applies in these contexts, the HIPAA protections are going to be more limited.”

Another common tactic the organization has seen in its work is law enforcement using women’s personal data to find evidence.

“When you do have someone who presents with a pregnancy loss and the police or prosecutors are trying to build a case that there was a self-managed abortion,” Sussman told CNN, “what they will look at is one’s digital footprint … who they communicated with and when and about what, what they searched, for purchases they made, credit card bills.”

She predicted that this sort of digital evidence “will be the thing that prosecutors will need in order to make that distinction, if they are going to try to distinguish between a miscarriage and a self-managed abortion.”

In the Mississippi case, investigators secured a warrant to search the phone of Latice Fisher, a Black woman who had experienced a stillbirth at her home in 2017. To bring the charges, they pointed to data showing she had searched for abortion pills earlier in her pregnancy (there is no way to medically test whether medication abortion drugs are in woman’s system after a miscarriage or stillbirth, since the drugs are usually metabolized more quickly than the time it takes for the fetus to expel). To build the case against Fisher, investigators also relied on a test known as the “lung float test,” a controversial method for investigating allegations of infanticide that dates back to the 17th century and that has been discredited by many medical experts.

Fisher’s lawyers pushed back on the use of the “float test.” After prosecutors reviewed the questions about the reliability of that method, as well as other allegations about Fisher that they found to be uncorroborated, they dropped the original indictment. When they represented the case to the grand jury with more context around the evidence, the grand jury declined to bring new charges against Fisher.

Laurie Bertram Roberts, the co-founder Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund who assisted with Fisher’s defense, equated investigators use of Fisher’s internet search to a “thought crime.”

“Let’s say at two months, I’m thinking about having an abortion and I search for stuff. And then I decide not to, and then I have a miscarriage at four and a half months,” Roberts told CNN. “That’s the risk, right? Lots of people think about having an abortion and then don’t.”

Who will get targeted with prosecutions

Legal and historical experts on abortion bans also expect that the bulk of enforcement will fall on marginalized communities that already face the brunt of policing — with some comparing it to the War on Drugs.

“The likelihood of being caught up in this police web is going to be higher for people of color and for lower income people,” Reagan said.

Oberman said that in her research of El Salvador’s extremely robust enforcement approach, there were still only around 10 convictions a year, in the face of an estimated 30,000 abortions that happen annually in the country. She said that a woman’s background is what authorities in El Salvador will look at to discern whether her pregnancy ended naturally or was purposefully terminated.

“Doctors in those cases tend to suspect patients whose storyline would suggest reasons to want an abortion,” she said, such as rape victims, single mothers or those living in gang-infested territories where their personal safety is at risk. “The cases that get reported out are the ones against the poorest and most marginalized folks in society. And the cases that prosecutors move forward on are similarly those where they can tell a story about motive.”

Local prosecutors who overstep the law

Anti-abortion activists say they have been consistent in their approach not to aim criminal anti-abortion laws at the woman obtaining the abortion, and that the directive will remain at the forefront if Roe is overturned.

“I do know we’ve seen pretty much across the board, with very few exceptions, a real commitment of lawmakers to make it clear that the woman cannot be prosecuted,” said Katie Glenn, government affairs counsel for the anti-abortion group, Americans United for Life.

Jason Rapert, an Oklahoma lawmaker who sponsored a “trigger” abortion ban that will go in effect in the state if Roe is overturned, dismissed the idea that women will be targeted, calling the concerns “a new false flag that’s being thrown up just to raise an issue.”

Asked how investigators will determine whether a miscarriage was natural or a medically-induced abortion, Rapert said that “You’re also talking about the honesty of the person.

“And I believe that people will be able to discern what is a miscarriage and what is not,” Rapert, who is also founder and president of the National Association of Christian Lawmakers, told CNN.

While it will be up to legislators to write the anti-abortion laws that they hope will end the procedure, carrying those laws will ultimately fall to local prosecutors.

A prosecutor in Texas Starr County attracted national attention this year for trying to charge a woman with murder for her self-induced abortion, despite the exemption in the relevant Texas law for the “conduct committed by the mother of the unborn child.” The prosecutor’s office said it was dropping the charges after a review the Texas law.

“In Starr County, the prosecutor initially and those that initially put the charges together, misunderstood and misapplied the law,” John Seago, Texas’ Right to Life legislative director, said. “And so that’s possible, but that’s possible with any crime.”

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2022 Cable News Network, Inc., a WarnerMedia Company. All rights reserved.