As the Supreme Court term draws to a close, the nation stands on the precipice of radical change. Any day now, the court will release its decision on race-conscious admissions — better known as affirmative action in college admissions.

The historic decision has the potential to alter the landscape of educational access and equity. Though no one knows exactly what day the Court will announce the decision, it will likely come by the end of June, when the Supreme Court term usually ends.

“The best guess is we know that the Supreme Court generally releases their high-impact decisions in early June,” says Dr. Sara Clarke Kaplan, the executive director of the Antiracist Research & Policy Center at American University. “That has, so far, borne out with this court.”

Experts have suspected that the primarily Republican-appointed, conservative-learning Supreme Court Justices will overturn 40 years of precedent and end explicit consideration of race in college admissions. But it isn’t that straightforward.

“Even though it is being predicted by many looking at the Supreme Court today, that is still an unusual step to take,” Cara McClellan, director of the Advocacy for Racial and Civil Justice Clinic, said during a Brookings webinar. “I just want to emphasize that for the Supreme Court to disregard precedent … is a highly unusual step and is an extreme action for the court to take.”

Here’s what’s on the table.

‘Shifted or Narrowed’ Parameters

Based on the history of the conservative court and last year’s oral arguments, it doesn’t “seem to bode very well for the future of affirmative action or race-conscious admissions as they currently exist,” Kaplan says.

Through conversations he’s had, Timothy Fields, the senior associate dean of undergraduate admissions at Emory University, believes race being considered in the application will be taken away.

“Schools are going to have to determine, in their selection process, how they’re going to find ways to try and identify students in a diverse way, but, at the same time, uphold whatever the new law is going to be,” says Fields, who also co-authored “The Black Family’s Guide to College Admissions.”

This will mostly hurt small schools, Fields predicts. Selective schools have the resources and larger applicant pools to find ways to ensure a diverse student body. But the question he has is when the new rules will be implemented, whether schools have a couple years to figure out new policies or if it will already apply to the next cycle of graduates.

Going forward, Kaplan thinks the options won’t be that race-conscious admissions will be overturned or upheld. Instead, she thinks the “parameters for it will be shifted or narrowed.”

What Race-Conscious Admissions Looks Like in Practice

Because affirmative action applies to more fields than education, it’s called “race-conscious admissions” when it comes to college acceptance, and it’s “contrary to what a lot of people think,” Fields says. It’s one of many data points that an admissions officer looks at, and people tend to give it a lot more importance than it actually plays in the process.

When looking at a student’s application, Fields sees a lot of information, all of which is taken into consideration: state, first generation, high school, GPA, classes, letters of recommendation, and extracurriculars.

And there isn’t a “quota system,” Kaplan says. Schools are not deciding to only admit so many white and Asian students, and then make sure they admit a certain number of Black students.

“There are all these multiple layers that we’re going through as far as making a decision, and race is just one of them. And it’s not a determining factor,” Fields says.

Race does not automatically grant admission. Instead, “it’s the same as somebody from Alaska or Hawaii is going to have a different lived experience than somebody from New York or Georgia,” Fields says. “It really is just additional information to find out who the person is.”

Misconceptions About Affirmative Action

There are many misunderstandings about how race-conscious admissions work aside from how it appears on an application. As Kaplan mentioned, affirmative action does not primarily benefit Black or Hispanic students. Instead, it’s been white women.

And the plaintiff in the case, Students for Fair Admissions, is not asking for other forms of identification to be removed from the application process, like gender, religion, or sexual orientation. They are only asking for race to no longer be considered.

“That is only going to have a disproportionate impact on students of color,” McLellan said in the webinar.

“I just wanted to complicate the idea that somehow the existing status quo is fair and neutral, because the ways that privilege is baked into admissions policies currently is only going to be exacerbated if we can’t consider the impact that race has on applicants,” McLellan said. “We know that race continues to shape applicants’ K-12 experience and can’t just be ignored at the moment that they apply to college.”

Another major misconception is that the majority of admissions being given through some kind of preference go to students of color through affirmative action, where the primary beneficiaries of these programs have been the “famous categories,” Kaplan says. These are “legacy” students, or those with family members who are alumni, students of major donors or athletes, and children of faculty.

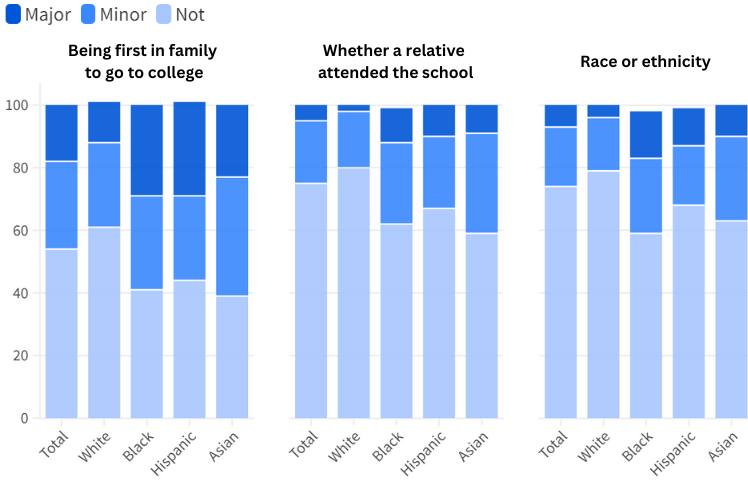

Nearly three-quarters of Americans think that race or ethnicity, gender, and a family member attending the same university should not factor into an admissions decision, according to a 2022 Pew Research Center poll. Instead, high school grades and standardized test scores were seen as the top two factors to be considered.

However, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American adults are all more likely than white adults to say these elements should be part of the admission decision.

While only 40% of white respondents think being the first in the family to attend college should be a factor, it rises to roughly 60% when polling Black, Hispanic, and Asian American adults. And Black, Hispanic, and Asian American adults are, on average, 12% more likely to say that race or ethnicity should be considered compared to white adults.

Black, Hispanic, and Asian American adults are more likely than white adults to say that race or ethnicity should be considered in college admissions decisions.

And, of course, these categories are disproportionately made up of white students and wealthy students.

“What we actually know,” Kaplan says, “is that most of the forms of preference in higher education admission benefit precisely the people who are now claiming that they are being discriminated against and excluded.”

A Broken System With Lasting Impacts

No matter what happens, Kaplan says, “what we’re looking at is a landscape that, at its heart, has the same question that we have been and should have been asking ourselves already” to create and ensure equitable access to higher education for people of color.

Currently, white women benefit the most from affirmative action. So the system as it exists is not producing equitable representation.

And, in states that have already overturned race-conscious admissions — like Texas and California — we’ve seen it gets worse. A 2014 study found that students of color experienced a decrease of 23 percentage points in likelihood of admission to highly selective schools.

“The numbers plummet,” Kaplan says.

And it has a lasting impact. It’s been proven in universities around the country that, after removing affirmative action, it’s a “slow recovery,” Dr. Kelly Slay, an assistant professor of higher education and public policy at Vanderbilt University, said during the Brookings webinar.

“Many years after these bans have been implemented, there are still persistent inequities in the enrollment of students of color across many different groups,” Slay said.

But it’s not just that students were unsuccessful in the admissions process. They’re making choices about the types of institutions they want to attend.

“Some of the research that I’ve conducted suggests that students are deterred from applying, even though they might have academic profiles that suggest they will be successful in the admissions process,” Slay said. “They decide to go to other institutions that they perceive to be more racially diverse and inclusive.”

But even so, affirmative action isn’t magic. Even with it in place, Black and Hispanic students are more underrepresented at top colleges now than they were more than three decades ago, according to a 2017 New York Times analysis. In 2017, Black students were 6% of college freshmen but 15% of all college-age Americans, a roughly 10 percentage point gap compared to 7 in 1980.

“However this decision goes down, it’s time for us to begin to band together,” Kaplan says. “And people are going to have to really think creatively and vigorously about what options we have for increasing equity and justice and access to higher education in terms of race, in ways that are entirely new models, because this model is not working.”

‘Higher Education Is Not Simply a Degree’

The country’s education system is not equal due to structural racism. And affirmative action was created to both correct histories of racial discrimination and to address those ongoing histories, from education to employment, that continue to play out, Kaplan says.

This means Black and Brown students don’t have the same access to schools that provide resources and rigor to make a college application stand out. And it’s important to ensure everyone is included so that there are multiple perspectives in higher education — be it race, ethnicity, religion, or politics — because it “mirrors the world that we live in,” Fields says.

“The underlying assumption is that there’s an even playing field, and there’s not right now,” Fields says. “We want to create a higher education system that people can access — not just close the door or only have it for a select few who have the means to go to independent schools, live in affluent school districts, participate in extracurricular activities, and all kinds of other factors.”

Those structural obstacles must be addressed in order to achieve equitable representation in higher education, Kaplan says. Otherwise, there will be a massive decrease in the representation of people of color, particularly Black and Brown folks, in higher education.

“It matters because we know that higher education is not simply a degree, but it’s actually the entry point for a huge number of other opportunities and life outcomes,” Kaplan says. “Higher education remains a crucial site for creating social, political, and economic opportunities for people.”