This article is one of a series of articles produced by Word in Black through support provided by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Word In Black is a collaborative of 10 Black-owned media outlets across the country.

For many educators, the 2022-2023 school year was harder than the pandemic years.

Sharif El-Mekki, founder and CEO of the Center for Black Educator Development, recalled a recent conversation with a principal describing the challenges.

“Every time there’s a shortage in your school, it has a ripple effect,” El-Mekki says.

If a teacher is absent, of course students’ routines and schedules are impacted. But it extends to their colleagues. What if there aren’t substitute teachers available? Who will cover the class? Then, losing that time means teachers have less time to prepare, build relationships, and reach out to families.

“There are so many different examples of that in the day-to-day lives of our teachers,” El-Mekki says. “But it’s not just teachers. It’s a whole ecosystem that has really been struggling.”

New Report Cites High Rates of Teacher Turnover

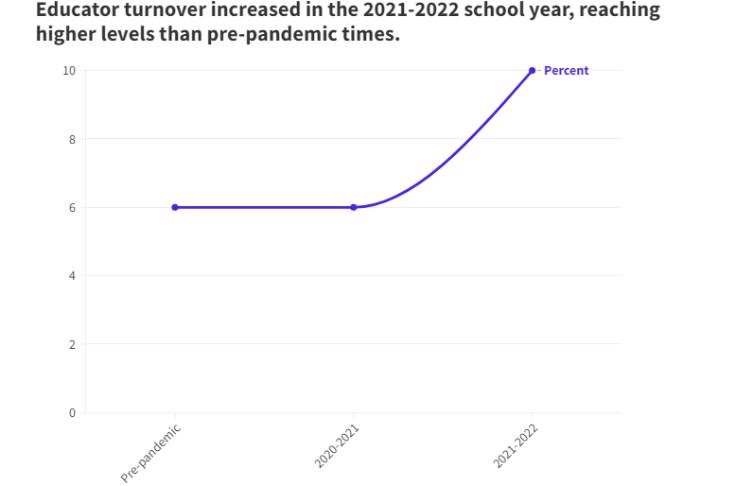

A new RAND report found that about 10% of teachers retired or resigned nationwide during or after the 2021-2022 school year, a 4 percentage point increase from the previous school year. These rates are now higher than pre-pandemic levels.

This is attributed to multiple things.

For one, people underestimate how the pandemic exacerbated inequities that already existed, El-Mekki says, like mental health.

A lot of mental health supports prioritize students, but “we also have to think about the vicarious trauma that the people who serve those students may be confronted with,” El-Mekki says.

“They’re human beings and part of the community — particularly diverse educators who may have also been impacted by COVID, and in significant and disproportionate ways,” El-Mekki says.

And teachers of color face additional challenges, says Dr. Fedrick Ingram, secretary-treasurer of the American Federation of Teachers. For one, many teach in zip codes that are more socioeconomically disadvantaged. And, of course, there’s the invisible tax — when Black teachers are expected to serve as disciplinarians or take on other responsibilities that don’t set them up for promotions.

Plus, with Black teachers making up less than 10% of the workforce, it’s common to be part of a very small group of Black teachers in a school — or even the only one.

“To ask our teachers to deliver on top of that, that could be a lot to bear,” Ingram says, “especially for a young educator who is really trying to come in and get their feet wet and trying to learn the art and science of education.”

Turnover Is Highest in These Districts

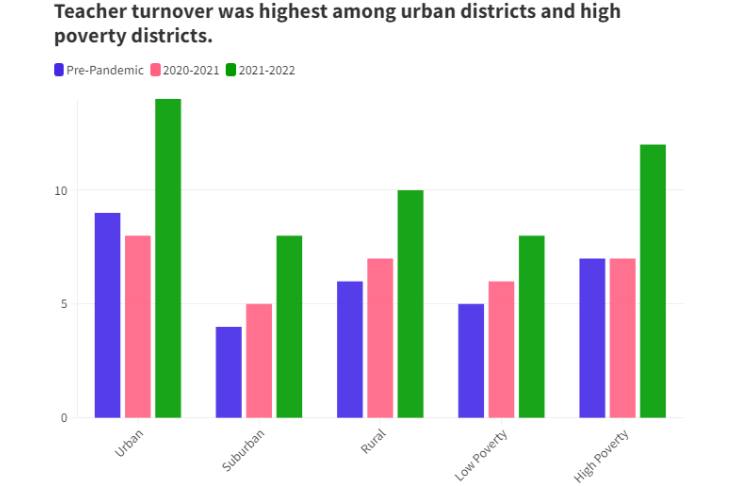

The roughly 114,000 vacated positions weren’t distributed evenly around the country.

Turnover was highest in urban districts (14%), the majority of which serve predominantly students of color, and high-poverty districts (12%).

And the turnover gap increased between majority white districts and districts with a majority of students of color. In the 2021-2022 school year, majority-white districts had a 9% rate of teacher turnover compared to 14% in districts with a majority of students of color.

These are all the districts that already needed support, El-Mekki says.

“Those are where the inequities have been the most concentrated for so long,” El-Mekki says. “Post-pandemic, there’s more challenges on top of what was already there. So it’s trying to build on top of inequity. Things are going to be compounded even more so.”

Wanted: Subs, Special Education Teachers, and Bus Drivers

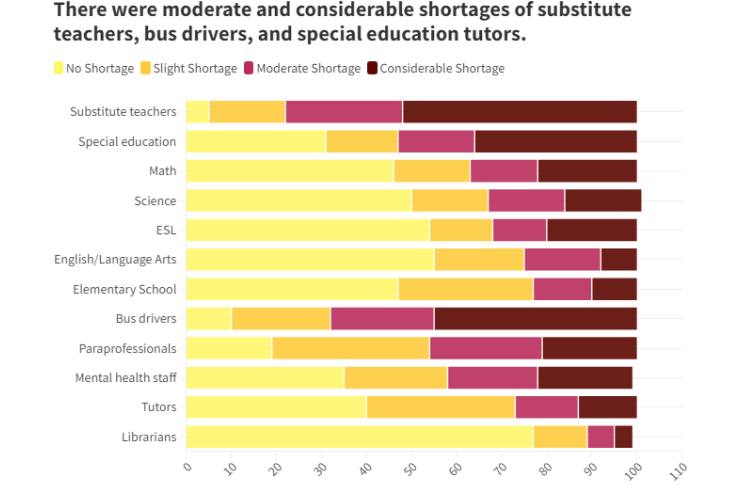

The most common shortages were among math teachers (38%), science teachers (33%), and English as a second language (ESL) teachers (32%).

The shortages weren’t limited to classroom teachers. Districts nationwide also reported moderate or considerable shortages of substitute teachers (78%) and special education teachers (53%).

And, about 68% of districts reported shortages of bus drivers. Since the pandemic, El-Mekki’s daughters have had two or three different bus drivers.

Bus drivers are generally the first people in the “educational village” that students see every day, Ingram says.

“We expect those bus drivers to have drinks and coffee and kick the tires, make sure they hit every stop sign and get those students there safely, and then get them back home in the same manner that they received them,” Ingram says.

They — along with cafeteria workers, paraprofessionals, and secretaries — are among the many in the educational village who deserve more respect.

These three categories are all jobs that “schools have historically had a difficult time finding,” the report says. And, Ingram adds, this has to do with there being “not a lot of relief” for those teachers.

“They started looking at other options,” El-Mekki says.

But the shortage of special education teachers isn’t a new pandemic-era problem. It’s a facet of the profession that requires a lot of paperwork, support, and specialty certifications. It can also be a more solitary job due to the lack of classroom assistants and fewer similarly-trained educators in the building, which leads to fewer professional development opportunities.

“If you have the students with the highest levels of need, and you’re getting the least amount of support,” El-Mekki says, “that can really fray your ability to be effective and your desire to stay.”

Looking at the 2023-2024 School Year

So what does this mean for the upcoming 2023-2024 school year?

“We are hearing that there are a lot of districts that are giving additional incentives to join the classroom or join their district,” El-Mekki says.

Some places in the country have succeeded at increasing teacher pay, and changing working conditions and contracts to better respect teachers.

And some schools are trying to restructure what supports and professional development opportunities look like and are available.

But, through all of the changes, nothing will matter if the voices of those who are meant to benefit aren’t being heard. And this doesn’t mean educators and bus drivers should be the ones drafting the policy, but they should be able to provide feedback or be involved in the conversations from the start.

“That would be the biggest miss, as districts around the country try to address these challenges and the shortages: Not listening to what’s happening on the ground, in the classroom, in the hallways, in the school,” El-Mekki says. “Too often, whoever’s furthest away from the classroom often is the one that signs off on policy.”

But, Ingram says, this is going to be a great school year. Some students will matriculate from one grade to another, and others will graduate. And teachers will do what they always do: “Stand at the gate of success for our students.”

“Our teachers are eternal optimists. That’s what we do,” Ingram says. “We believe that we can take a kid from one place to another if you give us the right time, give us the right space, get out of the way, and let the magic happen in the classroom.”

“That is what we’re going to do, and that is what happens every day.”