This article is one of a series of articles produced by Word in Black through support provided by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Word In Black is a collaborative of 10 Black-owned media outlets across the country.

by Maya Pottiger

“You have to promise me that you’re going to make sure he doesn’t get kicked out of school.”

This was the first thing a parent told Tara Kirton, who was working at the time as a one-on-one traveling teacher for special education preschool students.

Preschool suspensions have been studied since the late ‘90s, and rates have been relatively unchanged since then, according to a 2022 paper. Early childcare and education remain the “highest-risk” period for expulsion and suspension, the paper said, as children are three times more likely to be expelled during this time than during their K-12 careers.

Kirton experienced this both working in the classroom and when her own son was in preschool. It also helped shape her studies, as Kirton is both a doctoral student and full-time instructor of early childhood education at Teachers College, Columbia University.

While in a federal policy course, Kirton’s assignment was to think about an issue and how to tackle it from a federal education policy perspective. Preschool suspensions — and the “underlying parts of this conversation around anti-Blackness in education, implicit bias in education” — immediately came to mind.

Of course, it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, but “it cannot be on the backs of Black families, to put that onus of all the things that are wrong in early care,” Kirton says. “This is a systemic issue that needs to be looked at systematically.”

50,000 Annual Suspensions and Counting

About 250 students are suspended or expelled from preschool each day, according to the 2017 National Survey of Children’s Health. This adds up to about 50,000 preschoolers being suspended every year, with 17,000 expelled, according to the Center for American Progress.

And that astronomical number isn’t reflective of what actually happens.

“We think it’s way higher because there’s no true paper trail, there’s no monitoring and accountability system,” says Darielle Blevins, Ph.D., an assistant research professor at the Children’s Equity Project out of Arizona State University.

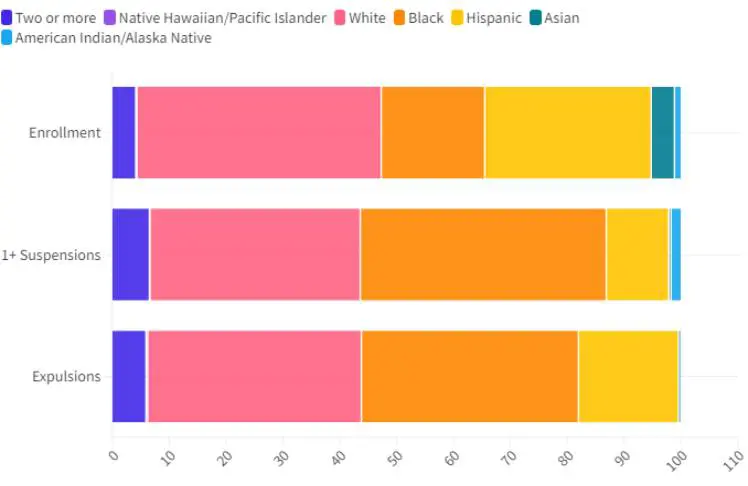

And those on-the-record suspensions are not equal. Black preschoolers were suspended 2.5 times more than their share of the total preschool population — meaning 18% of preschoolers are Black, and 43% of preschool suspensions were Black students, according to a 2021 report from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights. This rises to 48% when referring to students who were suspended more than once.

There were also disparities when broken down by race and gender. Black girls were the only group that accounted for more suspensions than their share of the enrollment.

Despite making up only 18% of preschool enrollment, Black students account for 43% of preschool suspensions and 38% of preschool expulsions.

And one of the more concerning pieces is that it isn’t getting better. With rates being unchanged for the last four decades, “this is basically something that is considered the norm,” Kirton says.

The preschool suspension crisis needs more awareness. And a way into that, Kirton says, is through the conversation around the United States population becoming “minority white.” With schools becoming majority students of color, it should prompt discussions about policy changes — or risk preschool suspension rates going even higher.

We need to “at least have these conversations,” Kirton says.

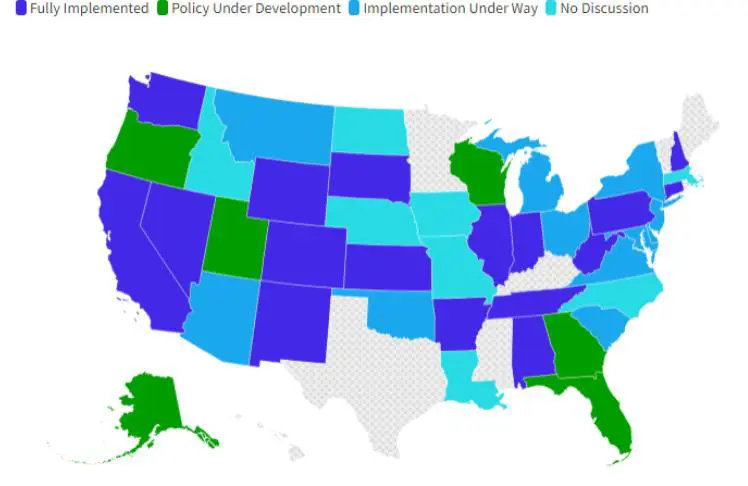

And there are states and programs — like Head Start — that are working toward this. Across the country, 18 states fully implemented policies reducing or eliminating expulsions and suspensions in early childhood education, according to a 2021 report by the National Center for Children in Poverty.

“As people are seeing the data more,” Blevins says, “we are seeing more states that are putting policy guidance around suspension and expulsions of young children.”

There are 29 states across the country that report having an expulsion and suspension policy in early care and education settings.

But change can’t happen if the conversations aren’t happening, Kirton says.

“Anytime I do have conversations with people, it brings about a lot of emotion and a lot of anger,” Kirton says. “It’s like, ‘Wow, these are the first experiences that we’re exposing children to? What will they then think of school?’”

No Longer Identifying as ‘Learners’

A 2020 report by the Children’s Equity Project says there isn’t evidence that harsh discipline improves children’s behavior, either in the short- or long-term, but there is a lot of research showing it has negative outcomes.

Children who are suspended in preschool are more likely to experience academic failure and be held back, have negative attitudes toward school, drop out of high school, and be involved with the juvenile justice system, according to a 2019 report published in ScienceDirect.

There’s no true paper trail, there’s no monitoring and accountability system.

DARIELLE BLEVINS, PH.D., ASSISTANT RESEARCH PROFESSOR AT THE CHILDREN’S EQUITY PROJECT

Students who are told from a young age that they are “bad,” or “misbehave,” or “don’t sit will” start to take on that persona.

“Children who are suspended at that young of an age while they’re developing their self-concept and who they are start to not identify as learners or scholars,” Blevins says. “Then they start to identify with whatever other message they’re getting.”

The ‘Draconian’ Thinking ‘Children Should Be Seen and Not Heard’

In preschool, the most common reasons for suspensions are being too disruptive — like excessive crying, inattention, or the inability to follow directions — or being too dangerous — like biting, hitting, or otherwise causing harm to themselves or others. In other words, common behaviors among 3-year-olds.

“We think about children, still, unfortunately, in almost a draconian way: Children should be seen and not heard,” Blevins says.

It’s like, ‘Wow, these are the first experiences that we’re exposing children to? What will they then think of school?’

TARA KIRTON, DOCTORAL STUDENT AND FULL-TIME INSTRUCTOR OF EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION AT TEACHERS COLLEGE, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

So, Blevins explains, children might be disciplined in the classroom for behavior that is accepted at home. In Black households, there’s a lot of overlapping communication with people talking at the same time. But, in a classroom, this could be considered disruptive and, therefore, grounds for suspension.

“You can end up being suspended, expelled, kicked out of class, told you are disruptive for doing something that’s culturally appropriate,” Blevins says.

Anti-Blackness shows up in classrooms in a lot of ways, including through the teacher’s implicit bias. Educators may automatically assume that Black children aren’t respectful, and that their behavior is threatening.

“Those ideas and those ideologies around stereotypes of Black men as dangerous are unfortunately overlaid onto children,” Blevins says. “And now teachers are viewing a little Black boy who’s having an age-appropriate tantrum as someone who’s a threat to the classroom.”

Navigating With Little Guidance

For elementary, middle, and high school, there is federal guidance on how to suspend students. But that guidance doesn’t exist for preschools.

“If you’re a mom-and-pop preschool who just opened down the street, you can do whatever you want,” Blevins says.

So what preschool suspensions often look like are a teacher or director saying the child’s behavior is inappropriate, and a parent has to come pick them up. And it can often come as a surprise to families, who generally aren’t part of these conversations.

There’s no formal process. There might not have even been anything written down.

DARIELLE BLEVINS, PH.D., ASSISTANT RESEARCH PROFESSOR AT THE CHILDREN’S EQUITY PROJECT

“There’s no formal process. There might not have even been anything written down,” Blevins says. “And they probably will never use the word ‘suspension’ because we still don’t view it as that for young children.”

Not naming it can be “extremely upsetting and extremely jarring” because you know the definition of what’s happening, but you are being told that what you’re seeing is different, Kirton says. “It feels like there’s been a breakdown of communication.”

What to Do if Your Child Is Suspended from Preschool

It can be life-altering if your child is suspended from preschool, and emotionally overwhelming.

“It’s important for parents to first start with self-compassion,” Blevins says, instead of immediately thinking something is their fault.

And her second piece of advice is to always believe your child. “We are trained to think that the school knows best and teachers know best. But in these situations, the child really may be treated unfairly.”

Here are steps to take if your child is suspended from preschool:

- Talk it out. Schedule a meeting “as soon as possible,” Kirton says. It would be best to do it in-person so “everyone is in the same space hearing the same message at the same time.”

- Take time to heal. If it’s an option and you choose to keep your child in the same preschool, know that there will be a healing process “because there has been harm done and trauma is there,” Kirton says.

- Know what you’re looking for. If you pursue another program, make sure you have an idea of what you want before you go on the tour. Do you want staff members who look like your family? What do you want in the environment? Are the bookshelves and posters reflective of your wishes? Can you talk to other families in the program?

When it comes to a preschool, it’s often a long-term relationship with people who you are trusting to care for your child and help them grow and develop, Kirton says.

“You want to know that, when times are great, we’re going to be happy, and we’re going to make this work,” she says, “but when times are getting a little tricky, I can still trust you to know that you’re my partner on this journey and that my child is safe with you.”

Kirton is gearing up for her dissertation study, which will further examine the experiences of Black children in preschool and daycare programs across New York City. She’ll talk to children and families to hear perspectives, and anyone interested in more information should email [email protected].