For the Black community, education is considered an investment, the best way for Black children to get ahead in life, and a key to overcoming systemic racism. But a new study indicates states are short-changing the schools Black children attend, worsening the achievement gap.

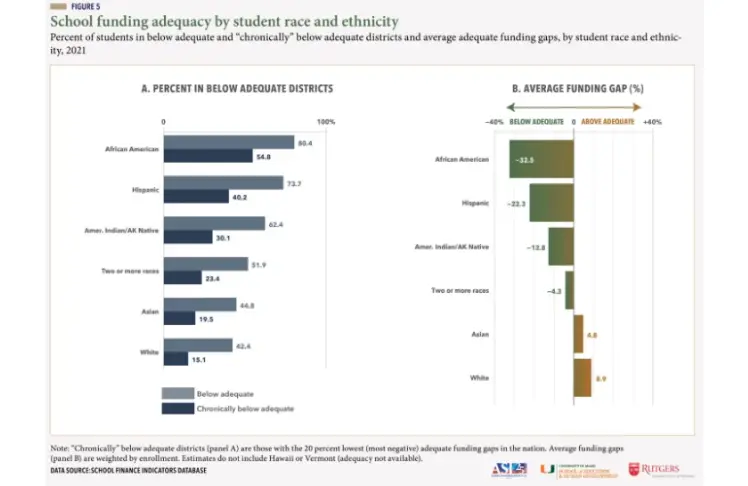

A study titled “The Adequacy and Fairness of State School Finance Systems” found that Black students are twice as likely as white students to attend school in districts with subpar government funding and more than three times as likely to live in “chronically underfunded” districts.

At the same time, researchers found that “educational opportunity is unequal in every state — that is, higher-poverty districts are funded less adequately than lower-poverty districts,” according to the report.

The funding disparities are likely to further increase “opportunity gaps” between Black and white children, creating what one researcher called “inequality factories.” And the disparities are occurring as school districts set academic achievement standards that children in underfunded districts often struggle to meet.

The findings, compiled by a team of researchers from the Albert Shanker Institute, the University of Miami, and Rutgers University, evaluated the K-12 school finance systems of all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The project analyzed data from 2009 — the depths of the Great Recession, during which revenue-starved states slashed education budgets — to the 2020-21 school year, roughly a decade after the economy recovered.

A thumbnail measure of education quality, school district spending varies across the country, with some school districts and states spending far more per pupil — and paying teachers more — than others. Yet spending matters: data has linked higher district spending to better student performance, test scores, and outcomes.

When the U.S. economy entered a sharp downturn, revenue-starved states slashed education budgets. But when the economy rebounded, however, not all education budgets bounced back.

“Good school finance systems compensate for factors states cannot control (e.g., student poverty, labor costs) using levers that they can control (e.g., driving funding to districts that need it most),” according to the study. “We have devised a framework that evaluates states based largely on how well they accomplish this balance. We assess each state’s funding while accounting directly for the students and communities served by its public schools.”

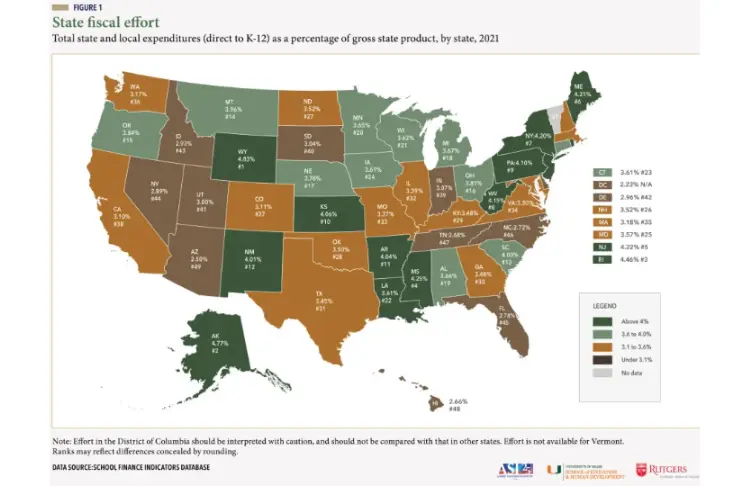

The framework found that in 2021, 39 of 50 states and the District of Columbia are spending less on public schools — what the researchers call “fiscal effort” — than they did in 2006, according to the report. The spending deficit, meanwhile, cost schools “over $360 billion between 2016 and 2021,” the report states.

Yet “most states have increased their expectations for the performance of schools, teachers, and students” without increasing funding needed to reach the higher benchmarks, Bruce Baker, a University of Miami professor and one of the report’s co-authors, said in a statement. The “permanent divestment” in public schools, he says, is a mistake by states who “have refused to make their districts whole after the disastrous cuts during that recession.”

The report also found that 20% of all U.S. public school students attend “chronically below adequate” districts, in which actual state funding is the furthest below adequate levels. But 60% of those districts are in just 10 Sun Belt states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, and Texas.

“The reality is that it costs more to achieve higher educational outcomes,” said Baker, “and we’re unlikely to see much return on our investments when we’re not really making those investments. And that goes double for low-effort states like Florida, Nevada, and North Carolina, which have the economic capacity to boost revenue but are choosing not to do so.”

Not surprisingly, Black students bore the brunt of the funding downturn.

Black students “are twice as likely as white students to be in districts with funding below estimated adequate levels, and 3.5 times more likely to be in ‘chronically underfunded’ districts,” according to the study. The discrepancies between Hispanic and white students, the report states, “are smaller but still large.”

The largest opportunity gaps “tend to be in states such as Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts,” where statewide spending adequacy is relatively high “but where wealthier districts contribute copious amounts of local (property tax) revenue to their schools,” according to the study. “This exacerbates the discrepancies in funding adequacy between these districts and their less affluent counterparts.”

Matthew Di Carlo of the Albert Shanker Institute, who co-authored the report, believes the opportunity gaps “are essentially inequality factories, with affluent districts funded to achieve higher student outcomes than lower-income districts, year after year.” And the inequality, he said, is a feature — not a bug.

“We cannot expect to close achievement gaps,” he said, “when states’ systems are designed to reproduce them.”

Bridging those gaps will require states to make a host of changes to district funding, including revamping district funding targets and increasing revenue, particularly state aid, according to the report. Researchers also believe the federal government must step up to help states that, due to high poverty and small economies, struggle to meet their students’ needs.