by Aziah Siid

Dr. Camika Royal isn’t a fan of public education.

“As somebody who has been an educator for 24 years, the more I study schools, the more I actually hate them,” says Royal, who is an associate professor of Urban Education at Loyola University.

“I see the ways they are used to further subjugate and humiliate the people who need school the most for social mobility and for liberation,” she explains. “Education is the practice of freedom,” Royal says.

As an urban education expert and the author of “Not Paved for Us: Black Educators and Public School Reform in Philadelphia,” she proudly identifies as a critical race theorist.

Her work is rooted in that awareness, especially as a professor at a predominantly white institute of learning. To that end, a major part of Royal’s work focuses on the intersections of race, politics, gender, history, and reform in the context of the past and present.

Part of this focus is ensuring all parties are held accountable for the role they play — or don’t — in the betterment of education for Black students. And while Royal says there are many issues in public education today, leadership and governance are the two that concern her most.

The Responsibility of Lawmakers

Royal’s referring to the numerous book bans happening nationwide, the refusal to teach true Black history, and attempts for state control over all levels of education.

“Leadership and governance, in some ways, won’t change the lived realities of teachers and students and classes,” Royal acknowledges. But “if you look at Florida, leadership, and governance have a whole hand in things being stripped.”

The problem isn’t just in Republican-dominated states like Florida, though.

“Philadelphians are not allowed to elect their school board,” Royal explains. “Public schooling should be a democratizing function of our American government, but they can’t even elect their own school board in Philadelphia.”

Royal says Philadelphia is the only school district out of the 500 districts in Pennsylvania where the school board is appointed by the mayor.

Leadership and governance are seen to be an obvious and brutal reality in many major cities, often cities filled with Black youths struggling academically, socially, and emotionally.

For example, in 2020, the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of five Detroit students who’d sued the state of Michigan and then-Governor Rick Snyder in 2016.

“Some young people sued these people, and they sued the state because they graduated from high school as functional illiterates,” Royal says.

But, as Royal points out, the first judge to hear the complaint dismissed the case in 2018, saying that literacy is not a fundamental right.

“The judge, in that case, ruled while schooling is compulsory, schools do not have an obligation to actually teach you,” she says.

Advocating for Black Children

“I think it’s important to continue to fight for public schools, but I also think parents and educators have to work outside of school settings to still get that same information and ways of thinking for students,” she says. “When the government wants to be fascist and tell you what can and can’t happen in school, they can’t tell you what can happen to your home.”

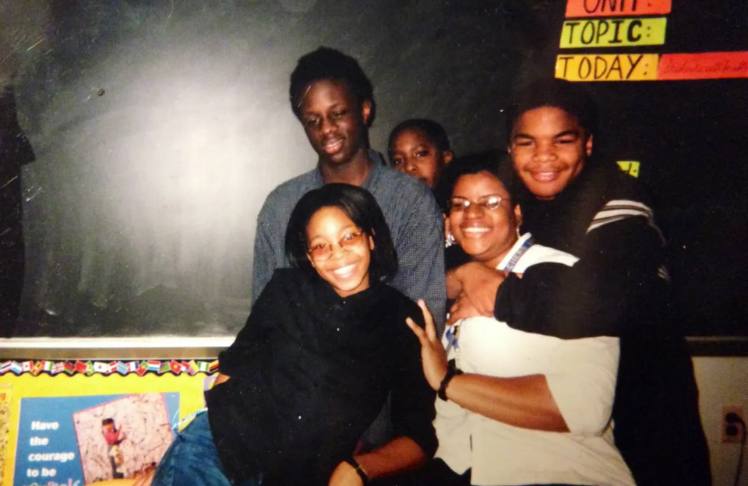

Royal, who is “Southwest Philly born, Penrose raised,” as she puts it, knows about this first-hand through her own mother’s fight against the system.

“My mother was very much an advocate,” Royal says. “She was not treated well as a student. That influenced how she worked with my sister and me in school.”

One story Royal vividly recalls is of a school dismissing her mother’s concerns about Royal’s reading level.

“She went to the school and was basically like, ‘Hey, I’m concerned my daughter isn’t progressing with her reading,’— and because she didn’t have a degree, she wasn’t qualified to question what they were doing with my sister at that school,” Royal says.

What Royal didn’t know then, and wouldn’t learn until college, was that her mother’s advocacy — combined with her own love for school — would transition into a passion for equity and opportunity for Black students in the future.

“I excelled at school very early. I didn’t need a lot of help. I loved it. I wanted to just absorb everything I was reading,” Royal says.

She also often asked questions, like why students frequently heard about Dr. Martin Luther King but not the other powerful figures in the context of civil rights and Black history as a whole.

“I also was a rabble-rouser and problem starter,” Royal says.

The Catalyst for a Career in Education

After graduating from high school in 1995, Royal found her way to North Carolina Central University, a public historically black university in Durham, North Carolina.

“I didn’t think I was going to be an educator,” Royal says. But then she found herself tutoring a first-grader who struggled with reading — and it shifted the trajectory of her career.

“You can’t help but tap into your own experience that you’ve had and be like, I want to do something about this,” she says.

Royal recalls the first grader being unable to sound out letters or decipher words without pictures, and he was fully aware of his inability to read.

“I asked him, ‘If I cover this picture, how are you going to read?’” Royal remembers. “He said, ‘Then I can’t read.’”

After graduation, Royal headed to Baltimore in 1999 to work as a seventh-grade language arts teacher.

“I wanted the troublemakers. I wanted the kids that other people said were a problem because I knew that that’s how I had been talked about,” Royal says. “I was also in over my head because I didn’t know what I was doing.”

During her second and third year teaching in Charm City, Royal unlocked a key many educators spend years trying to figure out: How to make students want to be there.

“In Baltimore, I asked my young people, what interests you? What do you want to learn about? What do you have questions about? What concerns you?” Royal says. “I allowed them to have an election, then created a unit around what they were interested in using our standards of learning, but also incorporating what they were interested in.”

Royal spent seven years as an urban education professional in Baltimore and later in Washington, D.C. She then returned to her hometown to teach pre-service teachers at Lincoln University of Pennsylvania, all while continuing to support and coach school teachers and leaders.

Cultivating a Culture of Resistance

One thing that’s stayed with Royal during her career is her mother’s resistance to the negligence of the school system — and Royal learned from her that there are ways to combat efforts that go against students’ fundamental rights.

Royal suggests that parents have books that address Blackness at home, and build up strong communities.

“This is where the community comes in. Communities coming together to say, OK, how are we going to teach our children this information, whether we’re in school or somewhere else?’” Royal says.

“I think we thrive in community,” she says. “It’s our responsibility to not spend so much time trying to compete with or to outdo our neighbor, our brother, or our sister, but to figure out how we can be in community and solidarity with each other.”

She also recommends that parents and caregivers create a presence at school. “We need to have more of us who will show up to the school so people know that you can’t just do anything with our children,” she says.

Royal’s taking her own advice. She’s currently on a sabbatical, so she’s using some of her time to establish a bigger presence at her nieces’ schools. She volunteers as a recurring guest reader in their kindergarten class.

Amplifying the Brilliance of Black Students

Much of the media chatter about Black youth in cities like Baltimore and Philadelphia revolves around concerns surrounding “ghost guns,” — or untraceable and unserialized firearms made right at home.

But when Royal comes across stories like this, she asks herself, what’s happening to these children before these guns land in their hands? Who is failing these kids?

“These kids are brilliant, and if somebody would actually pay attention to that in school, focus on that, then they can use their powers for good and not evil,” Royal says.

“Schools are absolutely missing the genius of Black children. The insightfulness of Black children,” Royal says.

“In fairness, a lot of times educators are overwhelmed with the sheer task and volume and complexity of teaching, learning, and some of the bureaucratic establishments,” she says.

Royal says part of tapping into the brilliance of Black students involves investing in an increased level of care and retaining quality teachers that understand the Black experience.

Giving the next generation of educators the tools to understand the intersections that impact students, while invoking the necessary amount of love and passion for the craft, is part of what keeps her hopeful.

“It’s always young people who give me hope,” Royal says. “It’s knowing that I am able to do some things and say some things my foremothers were not able to do. I think about how far we’ve come, and I look at our younger educators and young people and know that there is so much further to go and that I can hopefully pass the time for them and let them keep running.”