By the time Edafe Okporo arrived in Harlem in 2016, James Baldwin had been gone nearly three decades. Growing up in Warri, Nigeria, Okporo had read the Harlem Renaissance writer’s work long before he’d walk Baldwin’s streets.

“No matter where you go to, home is always where you feel safe and welcome — and home for Baldwin is always Harlem,” Okporo says. “I’ve been fleeing persecution my entire life, and I’ve been looking for a sense of home. When I came to Harlem, that was the first time I did feel at home.”

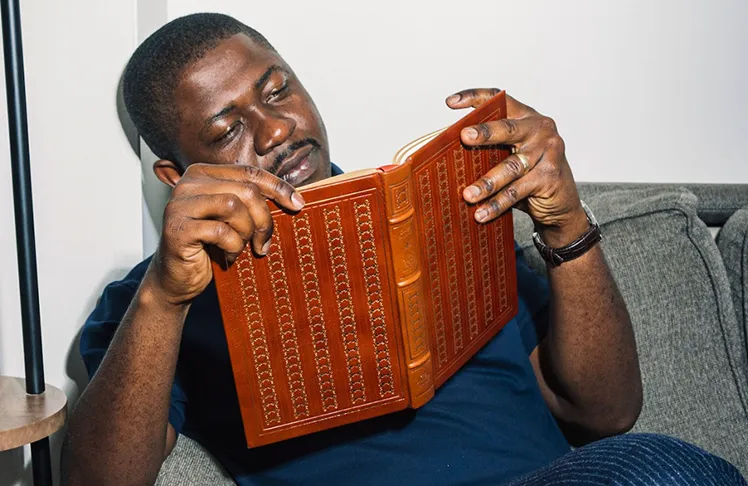

Indeed, almost a decade later, Okporo, who owns one of the 50 original gold-plated copies of Baldwin’s award-winning novel “Go Tell it On the Mountain,” says love — and the spirit of Baldwin — are fuel for his activism as a Black and gay refugee.

In 2020, he opened a shelter for asylum seekers — the first of its kind in New York City. Baldwin, he says, taught him not to be afraid to speak up about of the dangers of protest suppression, the ongoing conflict in Gaza that has left tens of thousands dead and an estimated 100,000 Palestinian women and children facing severe malnutrition, and the need for expanding access to PrEP to prevent HIV in marginalized communities — even when doing so isn’t popular.

And now he’s running for New York City Council in District 7.

“When I do this work of carrying the weight of my community in my heart, I feel like it’s a work that has to do with love rather than for the accolades of it,” Okporo says. “It is that love that is long-suffering, that is persistent, that comes at great cost, that leads us to change.”

Fleeing Violence and Persecution

After Nigeria’s Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill — which punishes LGBTQ+ relationships, activists, and organizations with 10 to 14-year prison sentences — was signed into law, a violent mob forced Okporo to flee. He sought asylum in the United States, but soon learned that prejudice and oppression exist here, too.

“In Nigeria, I was different for being a gay person,” Okporo says. “In America, I was not only different for being a gay person, I was different for being Black, gay, refugee, African, someone with an accent.”

RELATED: Reflections on James Baldwin at 100

“Be a Witness of His Time”

Okporo turned to Baldwin’s writings, seeking answers for how he could find safety, build community, and create opportunities for himself and others. Inspired by Baldwin’s ability to “be a witness of his time,” Okporo opened and operated the RDJ Refugee Shelter in Harlem for several years.

In 2022, he shared his story of emigrating to the U.S. through “Asylum,” a non-fiction memoir that serves as an honest guide for other refugees coming to America. And by running for local office, Okporo hopes to tackle issues he sees in the community, such as a lack of mental health resources and housing insecurity.

His touchstone through all of it has been Baldwin — and he believes more activists today can benefit from studying Baldwin’s speeches and reading his work. By doing so, Okporo himself learned that the fight for justice is not a singular event, but a lifelong pursuit because “our lives are inherently political.”

Life is full of contradictions, Okporo says. And justice “has to be a constant process.”