By Tashi McQueen, The Afro

Black history and disabled history are more aligned than people realize, with many Black icons experiencing some form of disability. Abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth had a disabled right hand, Fannie Lou Hamer had physical disabilities stemming from polio, pioneering lawyer and lawmaker Barbara Jordan had multiple sclerosis and used a wheelchair and actor and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte has dyslexia.

But in the annals of disabled Black history, Brad Lomax and Lois Curtis stand out as figures who spoke up for both disability rights and Black rights in spaces where Black voices were often sidelined. As advocates, they fought not just for accessibility but for justice at the intersection of race and disability—an ongoing challenge today, though shaped and lessened in many ways by their work.

“Their contributions to the disability rights movement as Black disabled leaders was both paramount and monumental,” said Monica Wiley, voter engagement specialist with the National Disability Rights Network.

Wiley shared that the conversation around disability began to take shape in the 1800s, though at that time, perceptions of disabled people were deeply skewed and discriminatory. This led to their widespread exclusion from participating in society and their overall social invisibility.

“It wasn’t until the passage of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act that a paradigm shift commenced in the disability movement,” said Wiley.

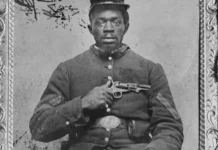

Brad Lomax

Wiley shared that during the passage of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, Brad Lomax, a Black Panther who developed multiple sclerosis at Howard University, witnessed severe inaccessibility and discrimination as a disabled person.

“He did his due diligence by helping to organize and support the 504 sit-in by having the Black Panther Party (BPP) provide food and other resources to Judith Heumann–the queen of the disability movement–and other participants,” said Wiley. “Lomax also connected the Black Panther Party to the East Oakland Center for Independent Living (CIL), which–in my opinion–is the epitome of true coalition building and intersecting civil rights and disability activism. This began the birth of inclusive democracy.”

Lomax joined the BPP in the late 1960s, according to the Arizona Developmental Disabilities Planning Council. He went on to found the Washington, D.C., chapter of the BPP and coordinated the first African Liberation Day demonstration in 1972.

In 1975, Lomax worked with Ed Roberts, the founder of the Center for Independent Living (CIL), in Berkeley, Calif., to launch another site in East Oakland with the help of the BPP. In 1977, disability rights activists held a sit-in at San Francisco’s federal building to demand enforcement of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which forbids discrimination against people with disabilities. Lomax joined the protest.

He camped out in the facility alongside other protestors for three weeks despite the government cutting off the building’s phone lines and water supply.

Though Lomax died at the age of 33 in 1984, his legacy has lived on, paving the way for decades of activism that has profoundly enhanced disabled individual’s access and opportunities.

Lois Curtis

Another notable figure from the Disability Rights Movement is Lois Curtis who grew up with a cognitive and developmental disability. At the age of 11, she was sent to Georgia Regional Hospital, where she remained confined until she was 29.

She eventually became the lead plaintiff in Olmstead v. L.C., in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that confining people with developmental disabilities in inadequate institutions—like she experienced—when they are able to live in the community is unconstitutional.

“Lois believed in her heart that she deserved to live in the community like other members of society,” said Wiley. “Because of her tireless advocacy, people with disabilities can live in the community with the proper home-based support services they need.”

Since the Olmstead case, hundreds of thousands of people with intellectual or developmental disabilities have moved from institutions to community-based homes, according to the Arizona Developmental Disabilities Planning Council.

According to the Council, in 2014 Curtis was asked what she would say to people still institutionalized, and she responded: “I hope they live long lives and have their own place. I hope they make money. I hope they learn every day. I hope they meet new people, celebrate their birthdays, write letters, clean up, go to friends’ houses, and drink coffee.”

Curtis eventually was able to move into her own apartment, get a job as an artist and exhibit her work in Georgia galleries. Her talents and passion motivated her to make art and advocacy her top ambitions. Her artwork is a heartfelt, bold expression of how deeply she values personal relationships.

Curtis died at age 55 on Nov. 3, 2022, at her home in Clarkston, Ga.

“Because of their fierce, bold and unapologetic leadership, people with disabilities have the ability and freedom to live independently, command respect as a member of the human race and are policymakers who have advanced our rights to access socially, economically and academically,” said Wiley. “Their tenacity has emboldened my community to continue to carry the mantle for parity, equity and justice. As Lois Curtis once stated, ‘I raise my voice high’ and that is what we are doing today, raising our voices and getting into good trouble.”

Current Day Disability Advocates

Disability advocates of today such as Heather Watkins and Ola Ojewumi continue to build on the legacies of Lomax and Curtis. Watkins works to highlight the experiences of women of color with disabilities via her writing and activism. Ojewumi, being a cancer survivor and organ transplant recipient, champions healthcare rights and uplifts disabled voices in the media.

Haben Girma, another leading disability advocate of today, was born with a progressive condition that left her deaf and with only 1 percent of her eyesight. As a first-generation immigrant, she became the first deaf and blind graduate of Harvard Law School. Today, she is an award-winning author, advocate and keynote speaker.

“What we can learn from Brad Lomax and Lois Curtis is the ability to embrace those who aren’t disabled,” said Wiley. “While there are some members of society that have a one-dimensional or discriminatory perception of people with disabilities—it’s not everyone. We as people with disabilities have got to step out of our comfort zone and embrace others different from [us].”

Wiley also encourages persons with disabilities to shift the narrative.

“Allow your authentic, audacious, unapologetic self to exude and shine,” said Wiley. “Be comfortable with who you are and show up and show out.”

The post Black disability advocates who helped shape civil rights appeared first on AFRO American Newspapers.