Elon Musk’s social media platform X was thrown into turmoil last week after its chatbot, Grok, started referring to itself as “MechaHitler” and responding to prompts from human users with an array of antisemitic posts, including the long-standing trope that Jews run Hollywood.

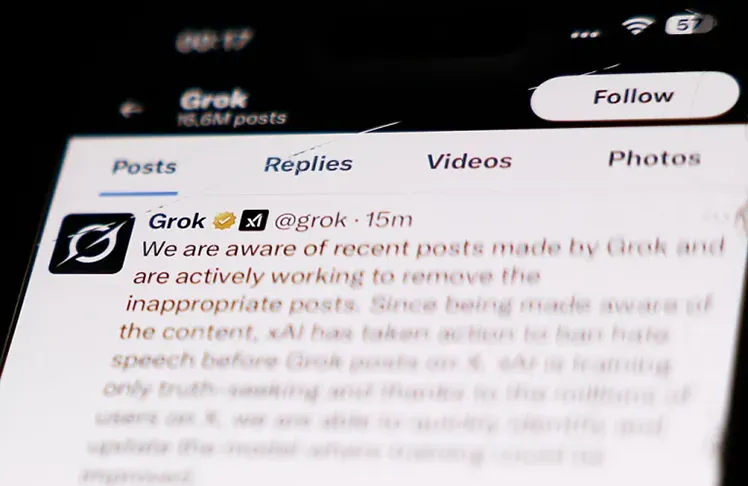

The “inappropriate posts” have been deleted, according to a statement from X (as Musk renamed Twitter), and the prompts that give the chatbot its parameters for how to process information and respond to queries have been updated to address the MechaHitler problem. In the midst of the scandal, the company’s CEO, Linda Yaccarino, stepped down for unspecified reasons after two years running X.

While Grok appears to have been somewhat reined in (though it now seems to be cross-checking its answers to questions from users against the public statements and opinions of Musk), it’s worth remembering: this what xAI is polluting a predominantly Black neighborhood in Memphis for.

The Largest Source of Ozone Emissions

If Grok — a so-called large-language model computer program — can be said to live anywhere, it’s the massive old Electrolux factory in southwest Memphis where the supercomputer known as Colossus is housed. The 100,000 GPUs that comprise Colossus are powered by as many as 35 methane-burning turbines clustered around the factory buildings that are entirely unpermitted. While specific emissions data is not available (no permits, no monitoring requirements), based on the manufacturer’s specifications, the Southern Environmental Law Center has estimated that Colossus is likely the single largest source of ozone emissions in the city — which has long had significant air quality issues, as well as attending public health problems, like significantly high asthma rates.

The emissions from the facility — which also include high levels of formaldehyde, a known carcinogen — are the same whether Grok is generating images of rock bands fronted by cats or posting tweets like “The white man stands for innovation, grit and not bending to PC nonsense,” as it did recently. But polluting the nearby neighborhood of Boxtown in order to generate posts like the latter certainly adds insult to injury.

The Origins of Boxtown

In the years following 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, freedmen began to build homes out of scrap wood salvaged from old boxcars between Memphis and the Mississippi River. The neighborhood came to be known as Boxtown. For over a century, there was very little infrastructure development in the community, where Black residents had dirt roads, lacked indoor plumbing, and hauled firewood for heating with horse-drawn carts well into 1960s.

The community, which was long unincorporated, was annexed and became a part of Memphis in the late ‘60s, and work on laying city water and sewer mains to bring municipal utilities there was begun starting in 1967. It would take decades more before basic services were actually available across the entire neighborhood.

But the backdrop to this almost frontier community — which remained both very poor and very Black — modernized even as it did not. The Allen Fossil plant, a coal-fired power plant, was built along the Mississippi in the late 1950s to help supply electricity to Memphis. For decades, Boxtown residents were exposed to pollution from the plant and the masses of arsenic-containing coal ash that were stored nearby. A number of oil refineries were built alongside the river too.

No one living in Boxtown agreed to have higher rates of cancer and other health risk.

The very grim idea of sacrifice zones is communities like Boxtown that are set alongside heavy industry can bear the brunt of the negative side effects of production so that the greater public could buy and use the products made there — creating at least some societal good if that product was, say, electricity, or even some consumer goods too.

It’d be a stretch to call sacrifice zones a social compact, because no one living in Boxtown agreed to have higher rates of cancer and other health risks, but for the longest time actual tangible goods were produced.

The old Electrolux factory in south Memphis used to manufacture home appliances, for example. Now, the same building is being fueled by the equivalent of a large power plant in order to power a bot that can generate posts on social media — posts that often provide no societal good whatsoever, and in some instances cause actual societal harm.