By Karen Ocamb

Black AIDS Institute

The first cases of what became HIV/AIDS hit the news on June 5, 1981. Soon, Phill Wilson, then just 25, and his new boyfriend Chris Brownlie were both diagnosed with swollen lymph nodes, which their doctor suggested could be related to the mysterious disease. But they were not afraid: the media widely reported that “GRID” (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency) was a White gay disease on the East and West coasts, or was contracted through poppers or by contact with “sexual athletes”—none of which they thought pertained to their lives in Chicago.

“Our doctor didn’t know much. No one had any information,” says Wilson. But then members of their gay softball team got sick and died in a matter of weeks. “That’s when it became real.”

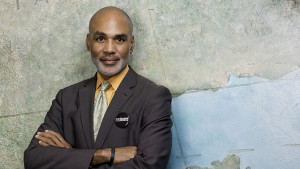

The epidemic, that has killed more than 25 million people worldwide, ended up engulfing Wilson’s life. He founded the gutsy and powerful Black AIDS Institute and became one of America’s foremost AIDS and gay-rights activists, featured in the new CNN docu-series, “The Eighties.” As he comes up to his 60th birthday, his lived experience shows how a person with humbled beginnings can stand up to almost anything, even a global plague.

Wilson and Brownlie moved to Los Angeles in the spring of 1982, started a Black giftware company and got involved in the gay and civil rights organization Black and White Men Together. “That’s when it got scary,” he says. “We had four or five friends sick at a time, most of them were Black. They didn’t look like any of them, the media was talking about. We realized that nobody gave a damn. Either we were going to die or we were going to have to fight, and still we might die. Die or fight or both. I had just met Chris. I had just found myself. I wasn’t ready to let either go. So, we fought and did whatever we could to not die—and to help our friends not die.”

It was a jarring epiphany—but Wilson was spiritually prepared for the fight. “When you are a poor Black kid in the 1950’s living in a housing project on the south side of Chicago, there is a lot your parents can not do or provide,” Wilson says. “But what they can do is to make sure you know that you are loved and you matter. That is what my parents did for me, my brothers and my sister. They knew they could not shield us from a racist world forever. Eventually we would hear messages that we were not OK—that we were the wrong color, our hair was wrong, or our noses were too broad. So they made sure we had some internalized protection—kind of like ‘PrEP for racism.’” He chuckled. “They wanted us to know our lives were worth fighting for.”

But even more important, Wilson says, his parents gave him a sense of responsibility for helping and understanding others, and an appreciation of his own privilege. When Wilson and his neighbor started kindergarten together, Wilson already knew how to read, tie his shoes, do some of the other things you learn in kindergarten. His friend, the middle child of 8 kids, a girl and dark, was not as prepared and was ignored by teachers while Wilson was perceived to be “cute” and favored. “My friend couldn’t do a lot of things the teachers were supposed to teach her to do. So I took it upon myself to help her,” Wilson says. But the teachers disapproved and separated them. Wilson told his parents how upset he was. “It was the first time I realized that people could be treated differently because of who they were, what they knew, or how they looked.” She eventually dropped out of school and became a teenage mother. “I blamed that kindergarten teacher. To this day, I believe I should have helped her more. I try to avoid that feeling.”

Survival and mutual responsibility are at the heart of the message Wilson conveys in his fight against AIDS. In 1986, Wilson volunteered to fight against the horrific Proposition 64 AIDS quarantine initiative sponsored by right-wing anti-gay activist Lyndon LaRouche—an initiative many feared would lead to branding, rounding up and putting people with AIDS into concentration camps. After the initiative’s defeat, Wilson and Brownlie worked with Michael Weinstein, Albert Ruiz, Mary Adair and others to found the AIDS Hospice Foundation—later to become the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, launching Wilson’s spectacular thirty-year national career fighting for LGBT and black civil rights and for people with HIV/AIDS. He served as the director of Stop AIDS Los Angeles, director of public policy and planning for AIDS Project Los Angeles, co-founder of the Black Gay & Lesbian Leadership Forum, AIDS Coordinator for the City of Los Angeles, member of the President’s AIDS Advisory Council, and the nation’s conscience as the founder of the Black AIDS Institute.

Few actually know how hard Wilson has personally fought to stay alive, taking every HIV drug as it became available (AZT, 3TC, D4T, and others), as did Brownlie. But science didn’t advance quickly enough to save Brownlie, who succumbed to AIDS in 1989. In 1997, Wilson landed on death’s door but refused to believe it was his time to die. The miracle of combination drug therapy saved his life, as it did for countless others, leading some to believe that the AIDS epidemic was over. But AIDS is still a crisis, especially in Black and Latino communities. According to the Centers for Disease Control, in 2014, 44 percent of estimated new HIV diagnoses were among Blacks, who comprise 12 percent of the U.S. population.1 in 2 or 50 percent of Black gay and bisexual men in the United States are likely to develop HIV in the course of their life time.

“Our house is on fire,” Wilson trumpets at every opportunity, hoping the community will hear and fight back.

The Black AIDS Institute is holding a fundraiser in celebration of Phill Wilson’s 60th birthday on Saturday, April 23. There will be great entertainment, surprise celebrity guests, and a roast. When asked what he wanted for his birthday, the birthday boy said, “I want to raise a lot of money for the Black AIDS Institute. I would like for all of my friends, family, and anyone who I’ve ever touched in anyway over the last 60 years to help the Black AIDS Institute finally end the AIDS epidemic in our community. The best way to start is by donating today!”