Special to the Trice Edney News Wire from New America Media

(Trice Edney Wire) – A drug that prevents HIV infection has been available for five years. But even in San Francisco, a city where one might expect information about the drug to be easy to come by, only some people have heard of it – and it’s not the communities that remain disproportionately affected by HIV.

“We don’t see Latinos, we don’t see Blacks, we definitely don’t see women and trans women as part of the imagery that’s promoting PrEP, so of course they’re not going to think it’s for them,” says Terrance Wilder of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

“We don’t see Latinos, we don’t see Blacks, we definitely don’t see women and trans women as part of the imagery that’s promoting PrEP, so of course they’re not going to think it’s for them,” says Terrance Wilder of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis, commercially called Truvada) helps prevent individuals who are HIV-negative from contracting HIV. It’s one part of a downward trend in HIV infections. In San Francisco, the rate of new HIV infections has decreased by more than 50 percent in the past five years, according to Michael Barajas, the citywide PrEP navigator at the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

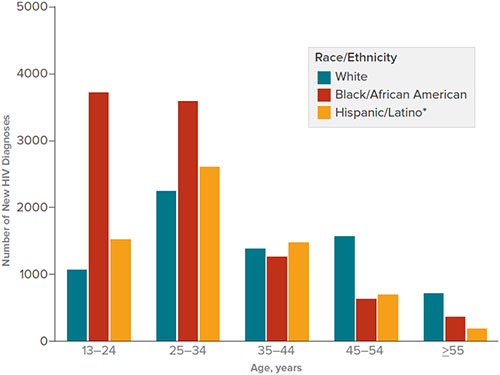

And yet, the CDC estimates that half of Black men who have sex with men (MSM), and a fourth of Latino MSM, will contract HIV over the course of their lives. In San Francisco, says Barajas, these populations account for a disproportionate number of new infections.

The San Francisco Department of Public Health has launched a campaign to close the information gap about the drug, and held a briefing for ethnic media where Barajas, Wilder, and other advocates spoke.

Most insurance plans cover the drug at least partially, and Barajas says that programs exist to help uninsured or underinsured people pay for it. His project, the San Francisco City Clinic, helps connect people with those programs.

But the bigger problem, says health systems navigator Jorge Vieto of the Glide Foundation, is that “most of the folks we’re working with don’t even know PrEP is available.”

Vieto, who works with people who are marginally housed, says that usage of PrEP is happening primarily among gay white men and that many of his clients think that’s the population the drug is meant for.

In addition, says LYRIC deputy director Denny David, “When you don’t know where you’re sleeping at night, the idea of remembering to take a pill is pretty challenging.” David’s organization works with LGBTQ young people; LYRIC has found that fewer than half of their clients have ever heard of PrEP.

Wilder coordinates a drop-in center in the Castro District called the DREAAM Project (“Determined to Respect and Encourage African American Men”) under the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

A lot of the young African American men he sees aren’t from San Francisco. They come to the Bay Area expecting to be liberated, Wilder says, but instead find a lack of housing and few economic opportunities.

“If you’re worried about other things like stability, I really don’t think you’re going to be worried about taking a pill every day. If every day you’re worried about where you’re going to lay your head and where your next meal’s going to come from … it’s going to be hard to think about daily taking this pill,” he says. “If you’re not in a good mental state, you’re not going to have the discipline to take those types of medications.”

There’s also the issue of stigma. Wilder encounters a lot of Black men who are “on the DL,” meaning that they identify themselves as heterosexual and may maintain relationships with women, but they also have sex with men. Wilder says the stigma and shame puts both these men and their female partners at risk: “They feel free with sex when they’re having sex with other gay men, which is [often] unprotected, and they’ll go home to their girls, and they’re not disclosing.”

Tapakorn Prasertsith, who supervises the HIV prevention program at API Wellness, says they encounter issues of stigma around the drug itself as well.

Among trans people, they say, especially among trans women, “the stigma is that [PrEP] has been presented as a gay drug, and trans women aren’t gay men.” Or, some clients think the drug is only for sex workers or people who habitually engage in high-risk sexual behaviors.

PrEP is for everybody, Prasertsith says, because HIV can affect anybody. It’s a message that prevention advocates say needs to start coming through.