This article is one of a series of articles produced by Word in Black through support provided by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Word In Black is a collaborative of 10 Black-owned media outlets across the country.

As K-12 students lay out their new outfits and pack supplies into their new backpacks for the new school year, roughly 1,100 students in Duval County, Florida, will be lacing up their new kicks, possibly in preparation for a long walk to school.

That’s because Duval County Public Schools recently implemented a new bus transportation policy where students living less than two miles from their assigned schools will no longer be eligible for bus transportation. In addition, the distance from a student’s home to their bus stop has been extended to half a mile.

The decision comes after it was reported last October that Duval County experienced a bus shortage of nearly 150 drivers, which caused massive delays for students, with some waiting more than an hour to be taken to school.

The Duval County School Board voted on the bussing policy change in May, a decision that aligned with state law. The Board was initially set to vote on making all students, including elementary schoolers, ineligible for busing if they lived within two miles of their schools, which would have saved between $500,000 and $1 million. However, in a 5-2 vote, it was ultimately decided to only apply to middle and high schoolers, saving between $250,000 and $500,000.

The shift has left many district families struggling to determine how their students will get to school safely. And the policy change in the county is no isolated incident.

Across the United States, school districts are grappling with reducing or eliminating school transportation services, using the ‘bus mile’ method. For Duval County, a school district that’s about 41% Black, such policies are nothing short of unfortunate.

The changes, often cited as cost-saving measures, underscore a pressing national crisis in public education: the confluence of budget cuts, transportation, attendance, and academic achievement and how it disproportionately impacts Black, Brown, and low-income students.

“Reducing school bus transportation for students, especially those from Black/low-income households, will present problems,” Dominique Jones, who studies education and public policy studies at Jacksonville University, tells Word In Black.

The Duval County School Board has yet to respond to Word In Black’s request for comment.

Two Miles Is Too Far for Many Parents

Although the policy applies to those who live less than two miles away from their school, students are looking at about a 30-45 minute walk — a distance too far for many parents.

“It’s insane,” parent LaToya Walker says. “What about the students whose parents don’t have a vehicle to get them to school?”

Walker says when a student has to trek two miles to school, that can “unfortunately lead to a lot of absences.” There’s also the issue of safety. “A lot can happen to a child in two miles,” she says.

Karli Olivia Gray-Pappas, a parent whose son attends GRASP Academy, a first through eighth-grade campus, says that while bus stops in Duval County have always been inconvenient, the new policy further frustrates parents with few options to ensure their children get to school safely.

“I never expected to live in a city where his school is 2 miles away and not be able to use the school bus. I also hate that he can’t experience it, as he always asks to.”

Kaysha Tomlinson, an early childhood educator and mother of five, also says that while the new bus policy didn’t affect her children, the change will further impact students’ absenteeism.

“It’s unfortunate for the children who really rely on a school bus. Two miles is too far for me, especially when it’s still dark outside,” Tomlinson says. “I already take my kids to school because of the bus option they had. I just felt it was too much of a hassle, and it wasn’t guaranteed that a bus would show up each day.”

Duval County School Board has yet to respond to Word In Black’s request for comment.

‘Bus Mile’ Policy Mirrors Nationwide Issue

Marginalized communities across the country — mainly Black and low-income families — often face disproportionate barriers to getting their children to school. Unreliable public transit forces low-income families — who often spend a significant portion of their income on transportation — to rely on personal vehicles or other transportation methods. This adds financial strain, increases student absenteeism, and reduces academic performance.

Last year, Zhaqueline Stewart, an 18-year-old senior at Westside High School in Augusta, Georgia, told State Affairs that due to cuts to school bus service, the bus she took was often late or broke down on the way to school, making her tardy so many times that it affected her grades. By the time she got to her first-period geometry class, “The important stuff, the instruction part, would be over,” she said. Ultimately, she ended up failing the class.

Starting this school year, students in the Sidney Public School district in Nebraska who live less than 4 miles from their school will have to pay to board the school bus.

And last year, families in Albemarle County, Virginia, were notified just weeks before the school year that students living less than 3 miles from their home school would lose access to bus transportation. Similar to DCPS, this change also impacted around 1,000 students.

Can School Bus Funding Be Fixed?

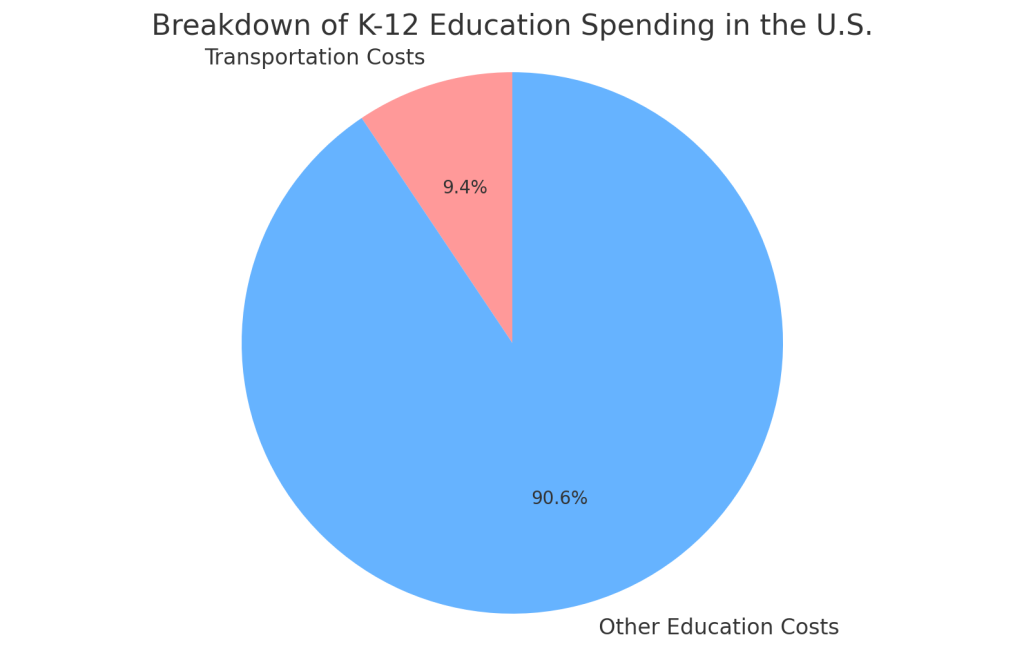

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, America spends more than $28 billion annually to transport slightly more than half of public school children to and from the classroom. That’s between 8 and 10% of the overall cost of K-12 education nationwide.

Some states directly fund schools’ transportation costs, while others require districts to cover these expenses using general aid from state or local sources. The state formulas and annual appropriations for reimbursing districts for the cost of bus services vary widely.

For example, in Missouri, the state is legally obliged to cover 75% of districts’ transportation costs, but it has only met this requirement a few times in the last three decades. In Georgia, the state’s contribution to school districts’ transportation costs has decreased from 50% at the beginning of the century to less than 20% in recent years.

In Illinois, school transportation requirements differ depending on the district’s location. Colorado is one of the states that does not mandate districts to provide student transportation to and from school, regardless of the distance students live from the school.

Since 1982, California has had fewer school buses than in other parts of the country, forcing districts and parents to shoulder more of the costs associated with providing transportation for students who live less than 1.5 miles from their school. A 2014 Legislative Analyst’s Office report highlighted how underfunded the state’s program had become.

A 2021 analysis in the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education on Black absenteeism in California, a state with the same bus mile policy as Duval County, also revealed that Black students tended to have more “unexcused” absences than their white peers. Nearly 53% of Black student absences were unexcused, with the researchers noting “transportation issues” as one of the major contributing factors.

In 2022, Gov. Newsom pledged state money to fund 60% of the cost of funding school transportation, the most significant increase in years. He also allocated $1.5 billion in one-time funds to help districts transition to electric school buses.

That same year, California State Sen. Nancy Skinner proposed a bill to provide universal access to school transportation for public school students through 12th grade. She argued that reliable school transportation could reduce chronic absenteeism and improve school performance, especially for low-income students. However, an analysis of Skinner’s bill found it would cost the state $1.4 billion, which may be why, despite support in the Senate, it didn’t advance.

Funding Football Stadiums

In addition to increasing awareness and proposing universal access to K-12 school transportation, Duval County community members also emphasized that funding public school transportation for all students isn’t being prioritized in the district.

In June, the Jacksonville City Council approved a $1.4 billion funding agreement with the Jacksonville Jaguars NFL football team to renovate EverBank Stadium. Of the billion-dollar agreement, the city of Jacksonville agreed to contribute $775 million in public funding.

Concerned community members like Rasheen Hawkins say that if Jacksonville can organize funds for football stadium renovations, then surely funds could be allocated to ensure that all K-12 students have access to bus transportation.

“To say that there’s not enough money to fund public school buses for all students, but there is public funding for renovating football stadiums makes no sense,” Hawkins says. “That’s not a ‘lack of funds’ issue, that’s a ‘lack of budget appropriation’ issue.”

“How do we live in a city where a football stadium has more financial resources than our kids?” Malik Washington, another concerned parent, asks.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Dominique Jones at Jacksonville University says that before districts look to eliminate services, they should consider “conducting an audit of existing bus routes to determine whether any could be consolidated or moved” before leaving families who are most likely already struggling to shoulder the cost.

“If transportation is necessary to access school and obtain a quality public education,” Jones says, “then we need to make sure we’re exhausting all efforts to make it accessible for students.”

Charlie Odell, a concerned community member, says the recent policy underscores ongoing issues and hopes the district will take more effective steps to address these concerns in the future.

“It’s time for DCPS to acknowledge its failures and take meaningful action to ensure reliable transportation for all students and address countless other issues, including budget shortfalls, safety, student achievement, and much more.”