As Sean “Diddy” Combs, who was recently arrested and charged with sex trafficking and racketeering, sits in federal custody awaiting trial, his three adult sons have rallied around him in New York. However, his 17-year-old twin daughters — D’Lila and Jessie — are in their senior year of high school in Los Angeles under the care of their late mother’s best friend.

Diddy’s legal troubles, combined with the loss of their mother, Kim Porter, in 2018, have left D’Lila and Jessie without both parents during a critical time in their lives. While the twins have financial support, their situation mirrors the harsh reality many Black K-12 students face: growing up in the absence of an incarcerated parent.

The twins’ current reality isn’t just about celebrity drama — it’s a reminder of the educational struggles children face when they lose a parent to the criminal justice system.

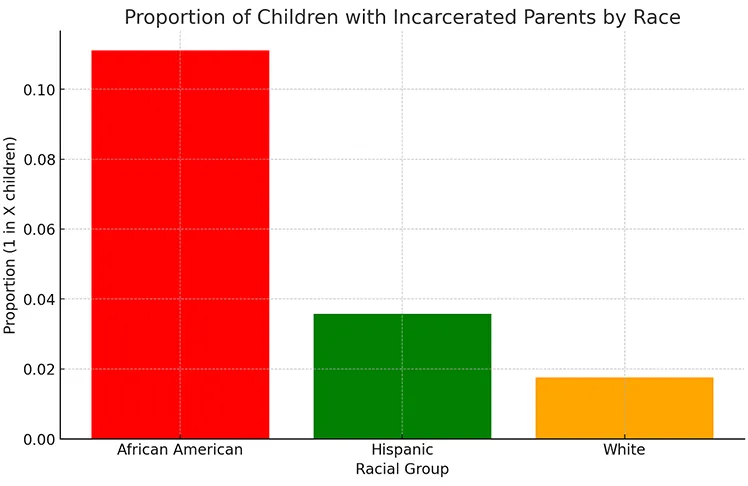

Parental loss due to incarceration is common among Black K-12 students nationwide. Recent statistics from the National Education Association and Bureau of Justice found that 1 in 9 Black children in the U.S. have an incarcerated parent, compared to 1 in 57 white children.

“I spent my entire childhood and adolescence visiting my father in different prisons,” says Emani Davis, director of The Omowale Project, a nonprofit organization designed to support Black folks and other people of color with sustainable individual and community care. “The Monday morning after a visit was always hard. I always cried on the way back home. And then I had to show up at school the next day, and teachers expected me to be present on top of being in school and feeling like you’re the only one going through it.”

Underestimating the Impact of Parental Incarceration

Students who lose a parent to incarceration, especially during their formative years, face several emotional, psychological, and economic hurdles that lead to a decline in school performance and heightened behavioral issues.

Dr. Howard Stevenson, a professor of urban education and Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania and a child clinical psychologist for over 30 years, says parental incarceration takes a toll on Black children, particularly in systems that fail to address their specific needs.

“Many children whose parents are incarcerated often struggle with the trauma of separation that isn’t openly discussed,” Dr. Stevenson notes. “They experience the absence and bear the burden of that loss in ways that can affect their academic and emotional lives profoundly. These children lack access to the kind of racial socialization that helps them navigate a world that is often hostile. That absence leaves them more vulnerable emotionally, without the tools to process that trauma.”

Jacksonville, Florida, resident Demarcus Lawrence experienced the incarceration of his father at age 9. “Watching other kids talk about their dads while mine was in prison was tough. I was embarrassed to tell my friends in school that my daddy was in jail and why. I acted out in school, and it only made things worse,” he says.

Dr. Stevenson also says that parental incarceration often leaves children vulnerable to emotional and psychological distress that can lead to poor academic outcomes. “The guilt children feel — thinking they are somehow responsible for their parent’s actions — is common,” he says. “And it adds to the stress of trying to perform in school while managing these overwhelming feelings.”

School Was a Terrible Place

The incarceration of a parent during one’s school years can have a significant effect on a student’s academic achievement. Research published in the Journal of School Health also found that implicit biases toward children with incarcerated parents can negatively impact their academic performance. This is especially true when teachers lower their expectations for the child.

“School was a terrible place for me,” Davis says. “They didn’t do a good job of asking the real questions of, like, why are we seeing these patterns of behavior or academic failure or struggle with this child and asking a much more well-rounded question about, like, what’s going on at home? So I think mostly, I was a problem for them, and they weren’t super invested.”

In addition, having an incarcerated parent is considered an “adverse childhood experience” — or ACE. A list of ACEs, which are experiences that lead to poor health outcomes, was developed in the 1990s by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Research shows school-aged children with an ACE history are more likely to be suspended, be absent, be less engaged with school, and have lower math and reading scores. However, Dr. Stevenson points out that this framework often falls short in its inclusivity.

“Some work has been done to add cultural factors to ACEs, but more needs to be done to include more culturally competent research on parental loss,” he says. Stevenson also emphasizes that the accumulation of these factors, such as parental incarceration, adds to the “load” Black students carry, often making it harder for them to thrive in school.

Dr. Stevenson also highlights that “the history of racism and exclusion, supported by legal and educational systems” has often been left out when diagnosing why Black children struggle, especially in cases of parental loss.”

“It’s not surprising because anytime we are failing, it has to be linked to criminalizing and dehumanizing us,” Davis says. “We still talk about it as if something is flawed with the child or the family instead of recognizing the flaws in the system. We’ve done little to soften how we demonize Black children in schools, and the narrative remains that there’s something wrong with them, rather than acknowledging the systemic factors at play.”

Advocating for Kids Is the Job of Adults

In the case of D’Lila and Jessie Combs, Davis reminds us that no amount of wealth can fully insulate children from the emotional toll of having an incarcerated parent.

“There’s nothing money can buy to change the impact of having their father publicly tried and potentially sent to prison,” she says. “Their lives are uprooted, and the emotional pain they carry is real and lasting, regardless of the resources they have access to.”

In advocating for Black students nationwide who have an incarcerated parent, Davis stressed the importance of community support. “Every system that touches children should be responsive and thoughtful about this,” she says. “The community needs to understand that advocating on behalf of children whose parents go to prison is the adult’s job.”

In addition, Davis says, we also need “schools that are more educated and supportive.”

Dr. Stevenson agrees that educating school staff is key. “We need more trauma-informed spaces in schools where educators understand the impact of these unique stressors and create environments that support emotional and academic recovery,” he says. “It’s not enough to expect resilience from children without giving them the tools and care they need to heal.”