This article is one of a series of articles produced by Word in Black through support provided by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Word In Black is a collaborative of 10 Black-owned media outlets across the country.

Screaming parents, students yelling racial slurs, and a law enforcement escort. That’s what the Little Rock Nine faced on September 25, 1957 when they made history as the first Black students to racially integrate Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas.

The nine Black students — Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Pattillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, and Carlotta Walls — entered the school under the protection of federal troops.

Reflecting on her experience in a 1999 interview, Melba Pattillo Beals described her fear walking through the angry crowd: “…It was absolutely terrifying to walk past them. Every moment I wondered what would become of me. It was the kind of fear I had never known. And it went on for most of the year.”

By bravely entering the school, the students challenged the longstanding lack of enforcement of the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision.

But even as we remember and recognize the bravery of the Little Rock Nine, the reality remains: too many Black students today face inequalities that echo the very struggles those pioneers fought to dismantle.

Racial Violence in Little Rock

Despite President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s deployment of federal troops to escort the students safely into the building, the Little Rock Nine endured a year of relentless harassment, isolation, and even physical violence at the hands of their white peers.

Elizabeth Eckford, whose iconic image of her walking alone through a hostile crowd remains etched in history, spoke about the obligation of the moment:

“Somewhere along the line, staying at Central High became an obligation. I realized that what we were doing was not for ourselves,” she told Newsweek in 1997.

Violent Opposition to Integration Was Common

What the Little Rock Nine went through wasn’t an isolated incident. In 1956, 12 Black students integrated Clinton High School in Clinton, Tennessee, becoming the first to desegregate a public high school in the South. The Clinton 12 faced violent resistance from segregationists in the town, and tensions escalated to the point that the school was bombed in 1958 by white supremacists in retaliation for the integration.

In 1959, public schools were shut down in Prince Edward County, Virginia, for five years to prevent integration, leaving Black students without formal education. Black families created makeshift classrooms in homes and churches until the schools were forced to reopen under a federal mandate.

In 1960, Ruby Bridges, at just 6 years old, became the first Black child to desegregate an all-white elementary school in the South. Bridges also faced threats, taunts, and isolation. For an entire year, her teacher taught her in an empty classroom.

Segregation in Today’s K-12 Schools

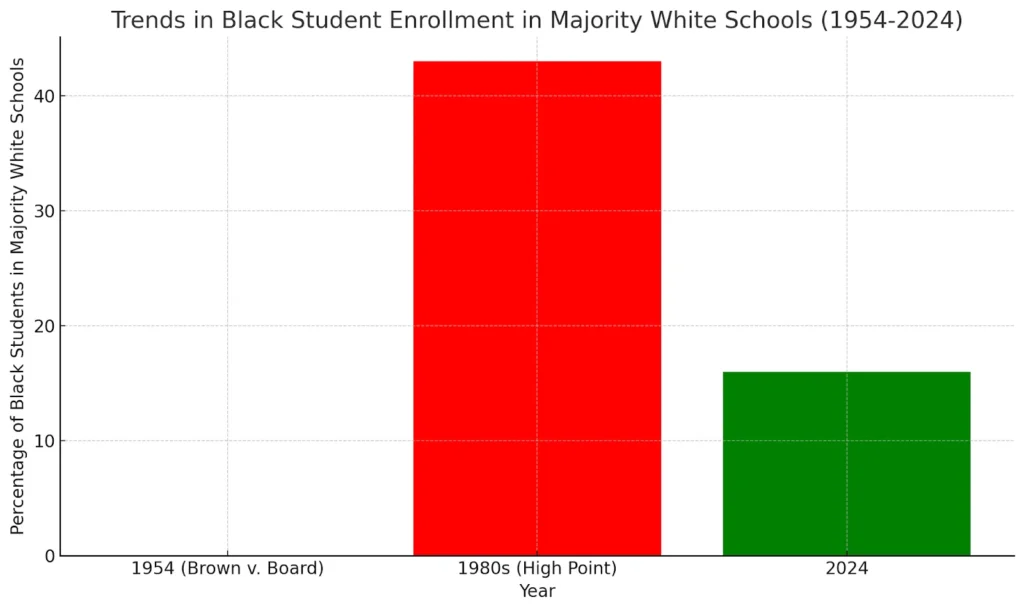

Significant change happened for Black people in all Southern states after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was enforced. At its high point in the 1980s, 43% of Black Southern students attended schools with white students, up from 0% when the Brown decision was decided in 1954.

However, a 2024 report by the Civil Rights Project at UCLA found schools in the United States are more segregated now than they were in the late 1960s. Only 16% of Black Southern students attend schools with white students.

Nationwide, Black students in the present day are often concentrated in underfunded schools with fewer resources, overcrowded classrooms, and limited access to advanced courses and extracurricular opportunities.

Segregation today is highest in our nation’s big cities, where Black students attend schools with an average of more than 80% non-white classmates.

An Ongoing Fight for Equality

The courage of the Little Rock Nine reminds us of the need for continued advocacy and reform in our educational system and that the fight for equality is ongoing — and is intersectional.

“Over the last 30 years, the proportion of schools that were intensely segregated (with zero to 10% whites) has nearly tripled, rising from 7.4% to 20%,” researchers at the UCLA Civil Rights Project found. “These schools are now doubly segregated by race and poverty with an average of 78% poor students.”

From ensuring equitable funding to dismantling discriminatory practices, the work to provide all students—especially Black students—with the education they deserve is far from complete.

As Carlotta Walls-LaNier, one of the Little Rock Nine, put it: “The road to success was through education. That’s the step I took at the age of 14 in signing that little sheet of paper to go to Little Rock Central High School. Any opportunity that comes along, whether it’s a crack in the door or the door’s wide open, you’re supposed to go through it.”