With millions of Americans seeking mental health care, we often forget therapists are humans, too.

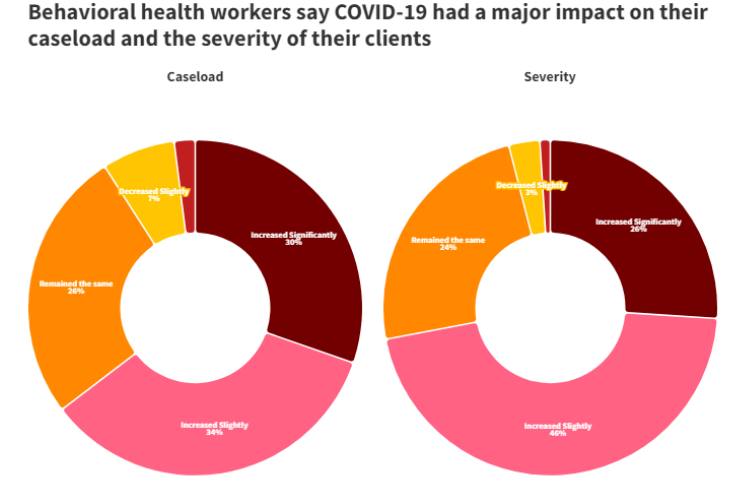

They are used to hearing about trauma, death, and life struggles but are not immune to facing those same challenges. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the increase of fear and death was paramount, leaving many to seek help.

But many mental health professionals cannot meet the demands of their jobs.

With workforce shortages and an overwhelming increase in clients, therapists are burnt out. A new survey by the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, conducted by The Harris Poll, found some alarming disparities.

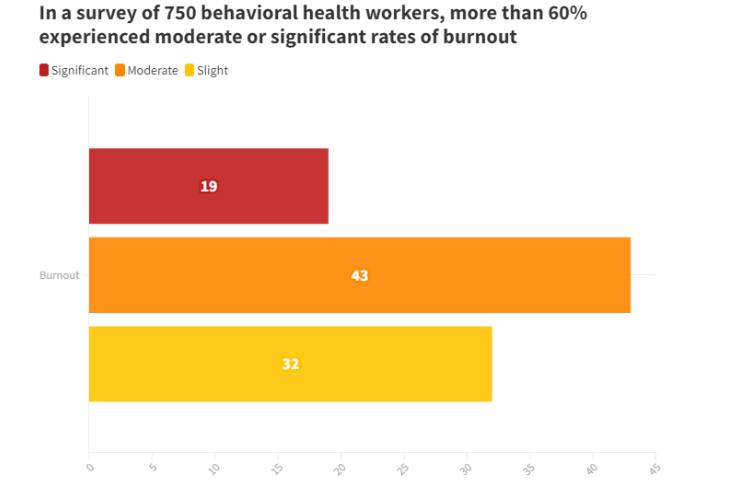

In a survey of 750 behavioral health workers, more than 60% experienced moderate or significant rates of burnout.

Michele Salomon, vice president of The Harris Poll, says the goal of the survey was to see how behavioral health professionals were managing their workload during the pandemic. She says it wasn’t surprising to hear so many respondents were experiencing burnout.

For Black mental health professionals, the struggle is even more real. Only 4% of therapists in the U.S. are Black.

They are used to filling the gaps and holes in a broken healthcare system not built for Black folks. Three therapists across the country said they feel the added pressure to show up for their clients because they know there are not enough Black therapists.

But what happens when Black therapists are burnt out?

Consider the first-person perspective of three therapists in Cumming, Georgia; Fresno, California; and Chicago, Illinois.

Shontel Cargill, MS-LMFT for 10 years in Cumming, GA

It took me years to realize I was experiencing burnout and compassion fatigue. Over time, I realized I was physically and emotionally drained. I began to sleep way more and never felt rested, leading to chronic fatigue and irritability. I started to develop migraines in my master’s program.

I noticed it the most during the pandemic. At one point, I thought, ‘Am I in the right field?’ It was so challenging to hold space for those experiencing trauma, grief, and even loss while trying to survive it myself.

Throughout my entire career, I’ve experienced burnout.

There were a lot of things that happened in 2020 that made it challenging to navigate. There was the George Floyd murder. I had also experienced a significant loss. I lost my daughter. And I almost died, myself.

I was diagnosed with postpartum PTSD, postpartum anxiety, and depression. I’ve never experienced burnout in that way. I felt like I couldn’t get my footing. Balance did not exist.

It’s ironic — helping others also makes me feel full. Later, I got trained as a perinatal mental health therapist. I wanted to show up for other Black mothers that may have had similar experiences.

That helped me with the burnout piece because I felt solidified in my purpose. I became the president of the postpartum support international Georgia chapter. That helped me prioritize self-care, set the necessary boundaries, and ask for help.

Burnout and compassion fatigue are very common experiences among healthcare professionals. The difference with Black mental health professionals is that we experience additional stressors, like systemic racism, discrimination, microaggressions in the workplace, and imposter syndrome.

There’s just so much more responsibility to ensure we’re taking care of ourselves to be present in therapy. We’re human first.

Some helpful strategies for Black mental health professionals would be to seek support from your village. Please release whatever that spirit tells you: asking for help is a sign of weakness.

Practice daily self-care: meditation, prayer, getting sun, getting enough sleep and rest, having a balanced diet, and regularly exercising. We have to allow our bodies to recover.

Jamal Jones, LMFT for 14 years in Fresno, CA

I was a substance abuse counselor at the Fresno County Jail, and we were understaffed. My own anxiety was out of control. I kept showing up for work, working overtime shifts, weekends, holidays, midnight crisis shifts, and rarely using any PTO.

I literally had a nervous breakdown on the job. I was placed on administrative leave.

I worked at the jail for about a year and a half. During the shift, I had a nervous breakdown; that was my last day working at that job. I didn’t have the best boundaries. I would say yes to different shifts, crisis shifts, and covering for other staff for an extended period of time.

That was just not sustainable for me. When you factor in the requirement to see 16 clients a day, more than 80 clients a week — it was just too much for me to handle.

If I could go back, I would be a lot more comfortable with being uncomfortable being behind. It’s just not realistic to meet everybody’s needs. As a healthcare worker, I think it’s important to know that you can’t help everybody as much as you would like.

When I was on leave, it felt great. My wife and I had a three-year-old daughter, and my life was out of balance because I had been working so much overtime. It was an opportunity to reconnect with my wife and to be more engaged with parenting our daughter. It was a time for me to get refreshed and renewed in body, mind, and spirit.

When I got the phone call from HR, I was informed that I was let go. That was heartbreaking and humiliating. I was shocked. It happened so fast.

Looking back, I see it as a blessing in disguise that I was let go. The experience I had there was invaluable. It has helped me to be more effective in my private practice.

Farah Harris, LCPC for 8 years in Chicago, Illinois

I feel like burnout can come in waves. It became more pronounced within the past year managing two businesses, three children, and writing a book.

Burnout, for me, looks like irritability. Just the overall frustration of seeming like there’s not enough time to get things done. I was short and less patient with my family. At times, it was difficult falling asleep.

I used my own emotional intelligence to ask myself what is it that I needed.

A big decision I had to make in 2020 was to close my private practice publicly. I wasn’t accepting any new clients at all. When it came to book writing, I had long gaps of time where I knew I couldn’t do well here.

When you are experiencing burnout, you have to see what’s on your plate or what’s on the table. Do they all need to be here at the exact same time?

I can’t teach people about emotional intelligence and not practice it myself. It was really important for me to hold myself accountable and recognize I needed to get off social media. And stop writing my book.

There is this narrative for Black women who are mental health professionals that we are to carry everybody else’s stuff.

I see this with my peers — there is this challenge with boundaries. If you are a mental health practitioner who is Black, specifically a woman, make sure you’re well. Take care of yourself first. You can’t pour from an empty cup; you have to pour from your overflow.

I think we can fall into the system of burnout because of that narrative that we want to help. We want to make everybody else feel better. We’re the leaders and nurturers, but we often don’t have that happening.

There’s the burnout from the emotional tax of being Black in these yet-to-be United States. I’m seeing clients, but I’m also experiencing the same stuff that they are — living in Black skin. This is why I say the systems of burnout. It’s hard to be the advocate and the abused.