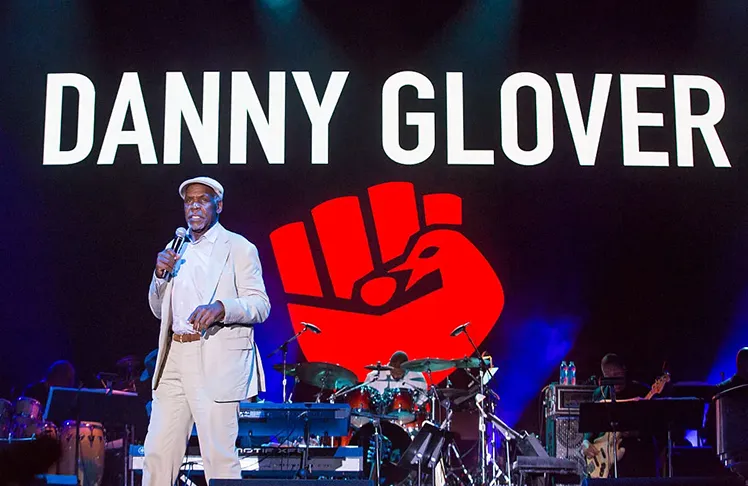

As we mark this Labor Day, polling shows that labor unions enjoy support from 70% of the public — an all-time high not recorded in the last 57 years. To celebrate American workers, we return to an interview with actor and humanitarian Danny Glover. Conducted by Unerased campaign director Gwen McKinney in 2017, Glover’s reflections on the centrality of organized labor in the overall fight for freedom and racial justice resonate as we mark Labor Day and new victories for our nation’s workers.

It started as a private conversation with my friend Danny Glover. He had just completed a protracted war in Mississippi, working with the United Auto Workers to organize a Nissan plant. As a fitting homage to Labor Day, I soon realized our discourse should enjoy a public stage. A living testament to arts and activism, celebrity is his megaphone. The protagonist of progressive struggle, Danny lives the tradition of his heroes Paul Robeson and Harry Belafonte.

Today, we’re gripped in a deep and disconcerting crisis of conscience. The soul of America is tattered and torn. Beyond partisan, racial, or geographic divides, the fault lines crack between those who long to Make America Great Again and those who imagine — in the hopeful spirit of one of our favorite poets — to Let America be America Again…(Never was America to me).

As we approach Labor Day, Danny Glover pours his passions into our chat about labor, movement, and change.

GWEN MCKINNEY: You describe yourself as a child of the labor movement. Talk about the early experiences that shaped you.

DANNY GLOVER: My outlook has been shaped by more than the labor movement. It’s the labor movement within the civil rights movement and the push for justice and racial equity. My parents both became postal workers in 1948. The post office was one of the most vibrant sources of Black employment and helped forge the early movement for equal employment opportunity in the federal government and private industry. This was the beginning of the modern civil rights movement and reflective of increased expectations for justice and opportunity among African Americans who fought heroically against Fascism abroad and were true patriots at home. My parents embodied that spirit. The politicization in our house profoundly affected me. I was 14 in 1960 when the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was formed; too young to join SNCC but inspired to become an activist in college a few years later. That backdrop fueled my activism, not only for workers’ rights, but also for Black power generally.

GM: What do you think is missing for people who did not grow up in a labor household like yours?

DG: Labor’s cultural atmosphere seeded an understanding of the collective rights of a community, a people. The labor movement unifies men and women around the value of working together collectively with respect and dignity. The movement was at its pinnacle after WWII. It gave ordinary people a seat at the table, honored a common appreciation for earning a living. Almost 40 percent of the labor force was unionized in the private sector, and the vast majority of Blacks moved into the middle class because of unions. For children of my era, the civil rights movement and the labor movement were synonymous. The climate had not transformed into what we see today – sustained attacks to undermine organized labor.

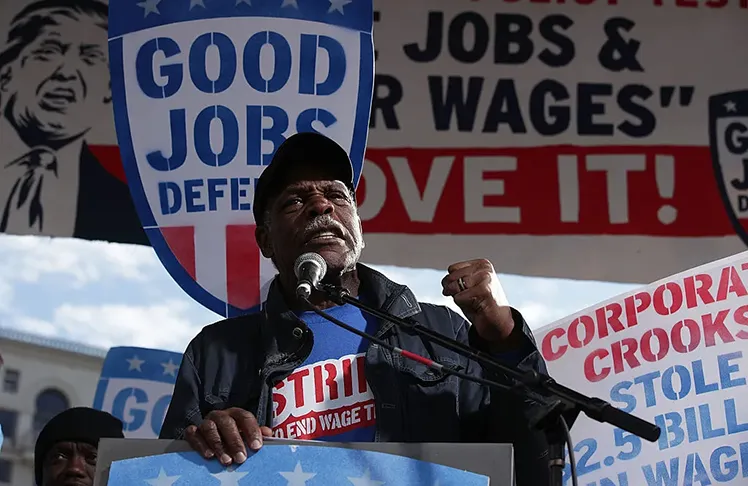

GM: You’ve spent a lot of time with the United Auto Workers to organize at the Canton, Mississippi Nissan plant. The UAW lost the recent vote for union representation, a crushing two-to-one defeat. What happened?

Editor’s Note: A fiercely contested election for UAW recognition was held at Nissan’s Canton, Mississippi plant, which the union ultimately lost in August 2017. The National Labor Relations Board cited Nissan for campaign violations.

DG: The loss would have been less difficult if the margin hadn’t been so wide. But Nissan launched a massive campaign, one of the most vicious I’ve ever seen, spending millions and allying with the chambers of commerce, the governor, the Koch Brothers. Their playbook was a microcosm of what has happened to unions and collective bargaining rights. The battle cry in Canton, where Blacks constitute nearly 80% of the workforce, was that you’re better off without collective rights. Otherwise, you will have no job; the plant will pick up and leave.

Racism was ever present, and the legacy of Mississippi loomed large. Look at Charlottesville and then contextualize what happened in a relatively isolated way in Canton. Opponents of the union tied to the KKK and Aryan Nation were openly broadcasting on the radio against the UAW. The governor declared that a vote for the union would ruin business prospects in the state. They actually made statements on radio talk shows like “You’re lucky to have this job. You could be out picking cotton or corn.” Despite the UAW framing of the campaign around the theme Workers Rights = Civil Rights, the union was unable to deal with the myriad tentacles of racism in a frontal way. The issues are broader and more complex than the message of that campaign theme. The Nissan workers also did not assess what they deserved or what they are entitled to. This has to do with how we see ourselves in this contemporary landscape and the disintegration of dignity and respect for workers.

GM: What is the takeaway from the UAW campaign?

DG: Nissan’s Altima is one of the top sellers for young Black urban Millennials throughout the United States. Perhaps a campaign should have linked to those young people. Should the message extend beyond the workers — a larger framework than jobs and working conditions? This also begs the question of the nature of unions in 21st-century America. Nissan has 45 assembly plants (not counting subsidiaries) worldwide. The only three that are not unionized are in the United States, not by accident, based in the South (Tennessee and Mississippi).

Over the last several years, men and women have taken on the global car industry, which has found a fertile ground in the right-to-work South. But without a signed contract, they have no leverage. We learned something from this campaign, which I hope will create conditions for necessary adjustments. And there must and will be a next campaign. The company employed scorched earth tactics, fear, intimidation, and buying off receptive backers in the community. The union has to win only one time. That becomes the template and sends a statement to everyone — opponents and supporters — that organizing is possible.

We’ve lost our sense of interconnection, and people of color have become even more marginalized. – DANNY GLOVER

GM: There’s been a lot of discourse about the blue-collar white male worker and the onslaught he has faced in recent years due to the decline in American manufacturing. Speak to this through your racial justice prism.

DG: Just drawing from the UAW experience, we recognized a significant number of auto workers (both union and non-union) voted for Trump. We cannot separate the status of working-class people from the impact of automation and globalization on job security and workers’ insecurity. Ironically, technology has put us out of touch. We’ve lost our sense of interconnection, and people of color have become even more marginalized. In states hardest hit by deindustrialization, white workers — all workers — are on the edge, especially workers who formerly felt secure. But Black and Brown workers have always been on the edge. The challenges have been intensified by a commodification of the individual in the most basic aspects of our lives — what we eat, what we wear, how we spend our time. Add to that “otherisms” framed as the source of the problem for white workers. The most important needs for them and all people who work for fair wages — collective strength, dignity, and respect — don’t matter anymore.

GM: How would you like us to observe Labor Day?

DG: That observance should go beyond the first Monday in September to the importance of working people as a platform to challenge racism and inequality, emphasizing the critical nature of fighting for labor unions and collective bargaining as a solution. Not just for workers of color, but for all workers. We also need to move away from glorifying the past and question what does labor look like in the 21st century…and what is happening here and now.

Lessons can be extracted from other struggles. The ILWU (International Longshore and Warehouse Union) refused to unload South African ships in 1971, sounding the bellwether of the U.S. anti-apartheid movement. The United Farmworkers, who boldly took on national and international growers, used many creative tactics to seed success. Labor cannot afford insularity or approaching struggles around narrow interests. Take the environmental space — deforestation, fracking, clean energy, mining, climate change — larger threats require new and imaginative approaches. The net gain (or loss) of jobs should not obscure the monumental demand to protect the planet.

Trump is just one of the manifestations of the national discontent. To his slogan “Make America Great Again,” my most appropriate response — as a tribute to Labor and working people — draws from one of our truly great Americans, Langston Hughes, who proclaimed, “Let America be America Again! Let it be the dream it used to be. Let it be the pioneer on the plain, seeking a home where he himself is free. (America never was America to me.)”

This post was originally published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform.

Gwen McKinney is the creator of Unerased | Black Women Speak and is the founder of McKinney & Associates, the first African American and woman-owned communications firm in the nation’s capital that expressly promotes social justice and public policy.