I promised our city that in 24 hours, I’d remove the monument that had haunted us for generations.

I had less than a day to do what lawmakers, activists, and lawyers couldn’t do over the course of dozens of years.

No pressure, right?

My team and I had to find a way to physically remove that massive structure, which seemed like a Herculean task in such a short amount of time.

Meanwhile, I had to play politics with the state.

I called both the state attorney general’s office and the governor’s office. I made my stance clear: If I had to choose between a civil fine and civil unrest, I was taking the fine. Birmingham was not having another night of unrest, not on my watch.

I knew there would be consequences, but I didn’t know how serious they could be. We were outright defying the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act. I thought to myself, “If I’m charged with a felony, I could be removed from office.”

I could be the architect of my own political demise.

Fear loves to whisper doubts into your ears. So what? I was too focused to hear it. I had to protect my city; that monument could not trigger another night of unrest.

We were one of the first cities after George Floyd’s murder to declare that a monument was coming down. And in less than 24 hours.

The governor’s office understood and didn’t push back. The state attorney general, though, fined us $25,000.

Whatever. We’d put up the bread. As long as that monument came down.

I have to shout out my team right here. I gave them a nearly impossible task—move a not-so metaphorical mountain in less than a day.

And they sprang into action without hesitation.

That morning, a structural engineer arrived to assess things. By that point, there had been a ton of damage done to the monument, so removing it safely was paramount.

The engineer knew the stakes were high. His hand trembled as he signed the contract.

Next up, we needed someone to knock the thing down, safely. And as we learned the night before, you can’t pull down a massive monument with a couple cords and a pickup truck. We’d need a crane to support the structure, a wiretooth saw, maybe a wrecking ball, several large trucks, the works.

Raising money wasn’t an issue—Birmingham’s philanthropic community graciously chipped in. One church donated $50,000 to cover costs. The real issue was finding skilled hands to do the job.

Remember, we were one of the first cities after George Floyd’s murder to declare that a monument was coming down. And in less than twenty-four hours. Many companies didn’t want to deal with that type of pressure. Plus, there was a big fear of retaliation.

Eventually, we found our crew: A general contractor from Mountain Brook, Alabama, a haul crew from Bessemer, Alabama, and a demolition crew from Cullman, Alabama.

Unless you’re a Birmingham native, it’s hard to convey how vastly different those three locations are. Mountain Brook is a city known for its affluence, while Bessemer lies on the opposite end of that spectrum. And until the 1970s, Cullman was known as a “sundown town”—a tag given to cities where Black folks weren’t allowed to live. We had to get out of town before sundown, or the consequences would be dire. These three different crews had never met each other. Frankly, they were nervous. But there was something astounding about these three very different walks of life uniting for an important cause.

It’s so very Birmingham.

By then, night had fallen, and time was ticking. We were racing against the clock.

We asked the crews to put cardboard over the logos on their trucks so they wouldn’t be identified. Meanwhile, Birmingham police secured the perimeter.

Media outlets were pissed—they wanted a front row seat. History was about to be made.

On the birthday of Jefferson Davis, the ex-President of the Confederate States of America, that damn monument, that 52-foot lie, finally came to the ground.

But again, my priority was protecting our teams. Tensions were still sky-high. Comments on social media were hostile. Anti-monument protesters were turned away, pro-monument protesters were turned away. There was another bomb threat called in.

The haul team was spooked. They hadn’t signed up for all this. But we convinced them to finish the job.

And they did. By 11:30 p.m. the obelisk was broken into three sections and the first piece had been removed.

On the birthday of Jefferson Davis, the ex-President of the Confederate States of America, that damn monument, that 52-foot lie, finally came to the ground.

Shuttlesworth would have had a big laugh about that.

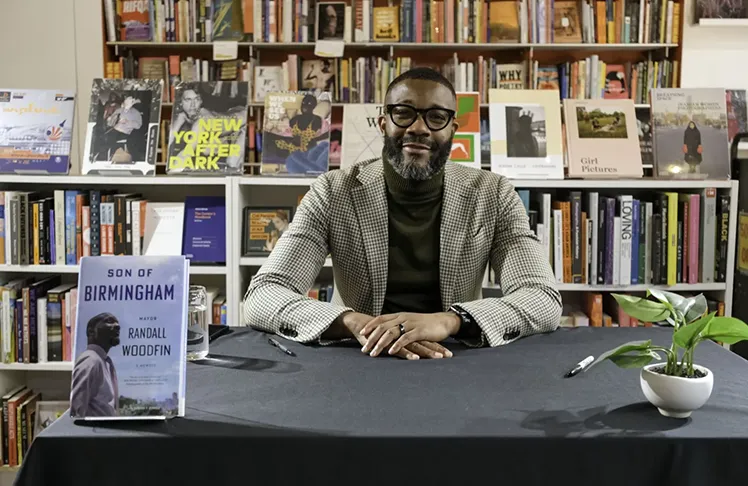

This is an excerpt taken with permission from the memoir “Son of Birmingham.”

Randall Woodfin was born in Birmingham, Alabama, and after four years in Atlanta where he earned his degree from Morehouse College, he has lived in Birmingham ever since. He worked at City Hall (in jobs for both the mayor and the city council) and for the Jefferson County Committee on Economic Opportunity, attended Cumberland School of Law at Samford University and, after obtaining his law degree, accepted a job in the City of Birmingham Law Department. As an assistant city attorney, he also became an organizer, working on campaigns at the local, state, and federal level. After serving on the Birmingham Board of Education, he ran for mayor in 2016 with endorsements from President Joe Biden, Senators Bernie Sanders and Cory Booker, and Stacey Abrams. Woodfin won an upset victory in a runoff in 2017 and earned a featured speaker role at the 2020 Democratic National Convention. He is seeking his third term in 2025.