By Shirley L. Smith

The COVID-19 pandemic and America’s continuing struggle with gun violence have shined a long overdue spotlight on the impact of grief on children. Child advocates are hoping this heightened awareness will spark a culture shift in American schools so that grief training and counseling will become as commonplace as active-shooter drills and recreational sports.

“What people need to remember is that active shooters are most often students. They are not strangers, which means that we have to think about how to create schools where we are connected to students, and create within schools a welcoming, supportive community that supports both academic achievement and student health and well-being,” said Kristen Harper, vice president for public policy and engagement for Child Trends, a nonpartisan research organization based in Bethesda, Maryland, in an interview. “If we narrow our conversation to what to do when the active shooter is at the door, it’s far too late.”

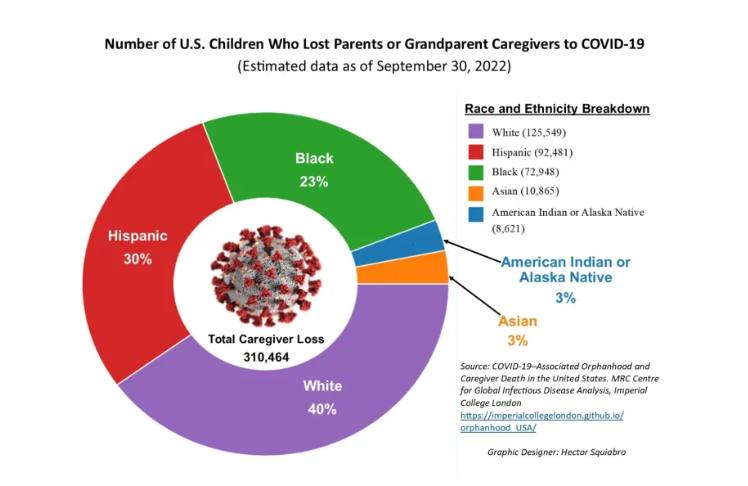

Since COVID-19 began its deadly assault on U.S. soil in 2020, researchers estimate that as of September, more than 300,000 children have lost one or both parents or a grandparent caregiver to the disease. Black and Indigenous children have the highest rates of parental and caregiver loss to COVID compared to their share of the population, followed by Hispanic children.

Many of these children were already drowning in grief and living in fear due to poverty related issues and gun violence, said Kevin Carter, a bereavement consultant and former clinical director for the Uplift Center for Grieving Children in Philadelphia, in an interview. The center provides free grief support services to children, families and schools. Most of its clientele are people of color experiencing grief, trauma and violence.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that Black and Indigenous families also have the greatest burden of death losses from gun violence and drug overdoses, both of which soared to levels not seen in years during the pandemic. In 2020, gun violence became the leading cause of death among children.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, explained in a Webinar on Oct. 4 that Black and brown communities have borne the brunt of COVID and other life-threatening diseases because of health care disparities. It will take “a decades-long commitment in neutralizing those health disparities, which are a result of social determinants of health that I believe are deeply rooted in the original sin of racism,” he said. “We’ve got to get over that and make sure that there is equity in our ability to get care to people.”

Social determinants of health, such as structural racism and poverty, have also been cited by the CDC as contributing factors to the disproportionate impact that gun violence is having on minority communities.

The CDC data shows that Mississippi, the poorest state in the nation, has the highest rate of gun deaths. A recent examination of FBI statistics by Empower Mississippi, a nonprofit advocacy organization, uncovered that more than half of the state’s homicides in 2020 occurred in the capital of Jackson, a predominantly Black community with poor infrastructure that EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan said in a statement is due to “years of neglect.” Mississippi also has thesecond highest rate of Black children who have lost a parent or caregiver to COVID. The homicide rate in Philadelphia, which also has high concentrations of poverty in minority communities, “escalated dramatically” since 2016, and 2021 was proclaimed by the city controller’s office as the “deadliest year in Philadelphia’s recorded history.”

“We certainly weren’t prepared enough for this increasing tsunami of grief,” Carter said. “We were in a crisis of neglect before the pandemic, because if we had better health care, better education, and if we were seen more as humans, I don’t think we would have had this disproportionate effect from COVID.” COVID exacerbated racial disparities that may have generational consequences if bereaved children do not get the support they need to help them through their long-term healing journey, he said.

Carter and other experts say schools cannot continue to expect the growing number of bereft children to carry on as normal when many of them are emotionally wounded from unresolved grief and trauma.

“Grief and loss training needs to be normative. More normative than football,” Carter said. “There has to be some recognition that this is a public health and a safety issue.” Overwhelming feelings of loss and fear can lead to rage, he said, and “that rage turns into sometimes consciously hurting other people or hurting yourself.”

Yet most educators are more prepared to deal with an active shooter than the multitudes of students who are going to school grief-stricken or traumatized from witnessing or experiencing the death of a loved one at home or in their community. Many educators are also unprepared to deal with the possible emotional fallout of active-shooter drills.

The advocacy group Everytown for Gun Safety reported that almost allK-12 schools in America conduct active-shooter drills, and at least 40 states require schools to do these drills, which vary from locking students in a room with the lights off to realistic simulations of gunfire and masked gunmen. Schools in Florida are required to do active-shooter drills every month.

School shootings, though tragic, are “relatively rare—accounting for less than 1% of the more than 40,000 annual U.S. gun deaths,” according to a study by Everytown for Gun Safety and the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Social Dynamics and Wellbeing Lab. The study “unveiled alarming impacts of active-shooter drills on the mental health of the students, teachers and parents,” but “limited proof of the effectiveness of these drills.”

“I used to have to put kindergarteners during a drill in the bathroom for 20 minutes with the lights off. That’s horrific,” said Amy Christopoulos, a former teacher and administrator with Miami-Dade County Public Schools, in an interview. She now works as the district’s homeless liaison. “Simulated drills can be scary for a 5-year-old. It’s very traumatic. Children were so scared that some of them peed in their pants.”

Although Christopoulos said she believes Miami-Dade is “ahead of the trend” in educating teachers on how to deal with mental health, she said “we spend so much time doing active-shooter drills, but we do not spend enough time on grief training and how to connect bereaved students to mental health professionals.”

Experts say children with unresolved grief and trauma also tend to act out, which can have serious consequences, particularly for Black students and students with disabilities, because they are more likely to be suspended, expelled and arrested.

“In my experience children of color are often perceived as more threatening and people respond to that perceived threat with control and punishment,” said Carter, who has 30 years of experience as a social worker.

“There have been cases where schools are calling Emergency Management Services and calling ambulances for children that act out, because they do not know what to do,” Harper said.

Maria Collins, vice president of New York Life Foundation, one of the largest funders of childhood bereavement in the U.S., said in an interview that only 15% of educators surveyed in 2020 stated that they had received training in childhood bereavement. However, 95% of educators indicated they “would like to do more to help grieving students.”

The foundation created the Grief-Sensitive Schools Initiative (GSSI) in 2018 “to better equip educators and other school personnel to support grieving students.” Schools that join the initiative are eligible for a $500 grant and opportunities for free grief training conducted by Dr. David Schonfeld, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician and director of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Collins said more than 3,900 schools have joined the initiative.

“I think grief training should be part of the core curriculum for educators, because kids come to school upset every single day and educators can’t just say they’re not ready to learn. They have to try and build the culture and climate in the classroom to make them more capable,” Schonfeld said in an interview.

He said they are not asking educators, who are faced with unprecedented challenges, to become grief counselors, just to become more informed about how grief can impact children so they can create a more conducive learning environment.

Losing a parent or loved one at an early age can significantly affect children’s emotional, social and behavioral development and overall health, Schonfeld added. “But I don’t want people to think that they’re destined to be damaged or lesser people as a result of it.” Unlike a mental illness, bereaved children generally do not need medical intervention, but Schonfeld stressed they need support and if they get adequate support in a nurturing environment to help them develop healthy coping skills, they can thrive.

Frank Zenere, school psychologist for Miami-Dade County Public Schools, said that the district joined GSSI about four years ago (following the deadly mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida) to increase educators’ empathy toward bereaved children. However, he acknowledged that there is still a lot of work to do.

There is a growing movement to make schools grief-sensitive environments. Frank Zenere, school psychologist for Miami-Dade County Public Schools and the district coordinator for the Student Services/Crisis Program, describes what a grief-sensitive school environment looks like. (Video produced by Shirley L. Smith)

While grief is a universal experience, it is one of the most uncomfortable things to talk about, Collins said, GSSI gives educators guidance on how to engage with bereaved students and furthers their understanding on how grief can affect children’s ability to learn.

Micki Burns, a psychologist and the chief clinical officer for Judi’s House, a comprehensive grief care facility in Colorado, cautioned in an interview that grief can mimic the symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), because bereaved children may have difficulty concentrating as well. “They may not be able to sit and focus for a 30-minute lesson and take in what’s being said by the teacher.”

On the other hand, bereaved children may get “so focused and so concentrated that they become a perfectionist, and they start to present as someone who is unable to fail, like I cannot fail,” Burns added. “Psychologically, that’s where we see the possibility of increased depression, increased anxiety and increased suicidal thinking.”

Despite evidence that school-based mental health personnel improve school climate and reduce violence, an analysis of the 2015-2016 school year by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) revealed severe staff shortages of school-based mental health providers and glaring disparities in school discipline in more than 96,000 public schools, which researchers say persist today.

ACLU analysts found that, “14 million students are in schools with police but no counselor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker.” These individuals are frequently the first to see children who are sick, stressed, traumatized, acting out, or who may hurt themselves or others, the report said.

School counselors have been saddled with heavy caseloads for over three decades. The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250 students per counselor, but the average national ratio for 2020-2021 was 415 students per counselor.

Vittoria Cianciulli, trust counselor for the largely Hispanic Miami Lakes Middle School in Florida, said in an interview that she serves 1,000 students. Her duties include assisting students with emotional and mental health issues and providing substance abuse and bullying prevention programs.

Cianciulli said she loves her job, but admits she gets frustrated because she cannot attend to the needs of every student, and she worries about students falling through the cracks. “It gets to be a lot, especially the responsibility. I just want to make sure I’m helping a child that is in crisis, that there is no one that leaves school and God forbid something happens to them.”

School psychologists are also stretched thin. The national ratio for school psychologists for 2020-2021 was 1,162 students to one school psychologist. This is well above the National Association of School Psychologists recommended ratio of 500 students per psychologist. Alabama has the highest documented ratio with an astounding 376,280 students to one psychologist.

The alarming increase in mental illness among children during the pandemic and the rise in gun violence prompted Congress to pass the landmark Bipartisan Safer Communities Act in June, which includes significant investment in school-based mental health services and staff. “It’s a huge step in the right direction,” Kristen Harper of Child Trends said. “Schools need consistent funding to build a sustainable infrastructure, but it is only part of the equation. Consistent funding does not alleviate the broader health and education inequities that put students in harm’s way.”

Harper added, “The conversation about school safety and student health tends to fall off the radar until a tragedy happens, which leads to reactionary policies that give the appearance of safety but have been proven to be ineffective like punitive disciplinary practices and ill-conceived active-shooter drills and school-based policing.” Educators need to develop “evidence-based” preventative strategies, she said.

“There needs to be a culture shift from an authoritarian, punitive culture to a culture of support,” Harper continued. At the heart of this shift is making sure schools have sufficient counselors and mental health professionals and building strong relationships between students and the adults in the schools, she said. “If children feel like they can trust a teacher or another adult within the school, they will tell them when something is wrong.” Schools should also make sure students’ basic needs are met, “so children aren’t coming to school hungry, and when they do, there’s food available for them.”

Harper insists this approach will create a safer school environment and ensure students struggling with emotional, mental or behavioral issues get appropriate care before they spiral out of control. “Students who feel supported at school are less likely to engage in risky behaviors like drug abuse and violence, or experience emotional distress.”

Kevin Carter echoed Harper’s sentiments for a less punitive system. “This doesn’t mean you should not give boundaries, but if adults are calm and understanding, then it’s probably less likely for a situation to escalate, and even if it escalates, maybe no one gets hurt, and that child will get the care that he or she needs.”

For guidance on how to talk to bereaved students, please visit: https://grievingstudents.org/module-section/talking-with-children/

This project was supported by the National Geographic Society’s COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists.